Portfolio: Olivia Bee

Photographer Olivia Bee: “Insignificant gesture becomes extraordinary when you’re giving it attention”

Lena Hervé

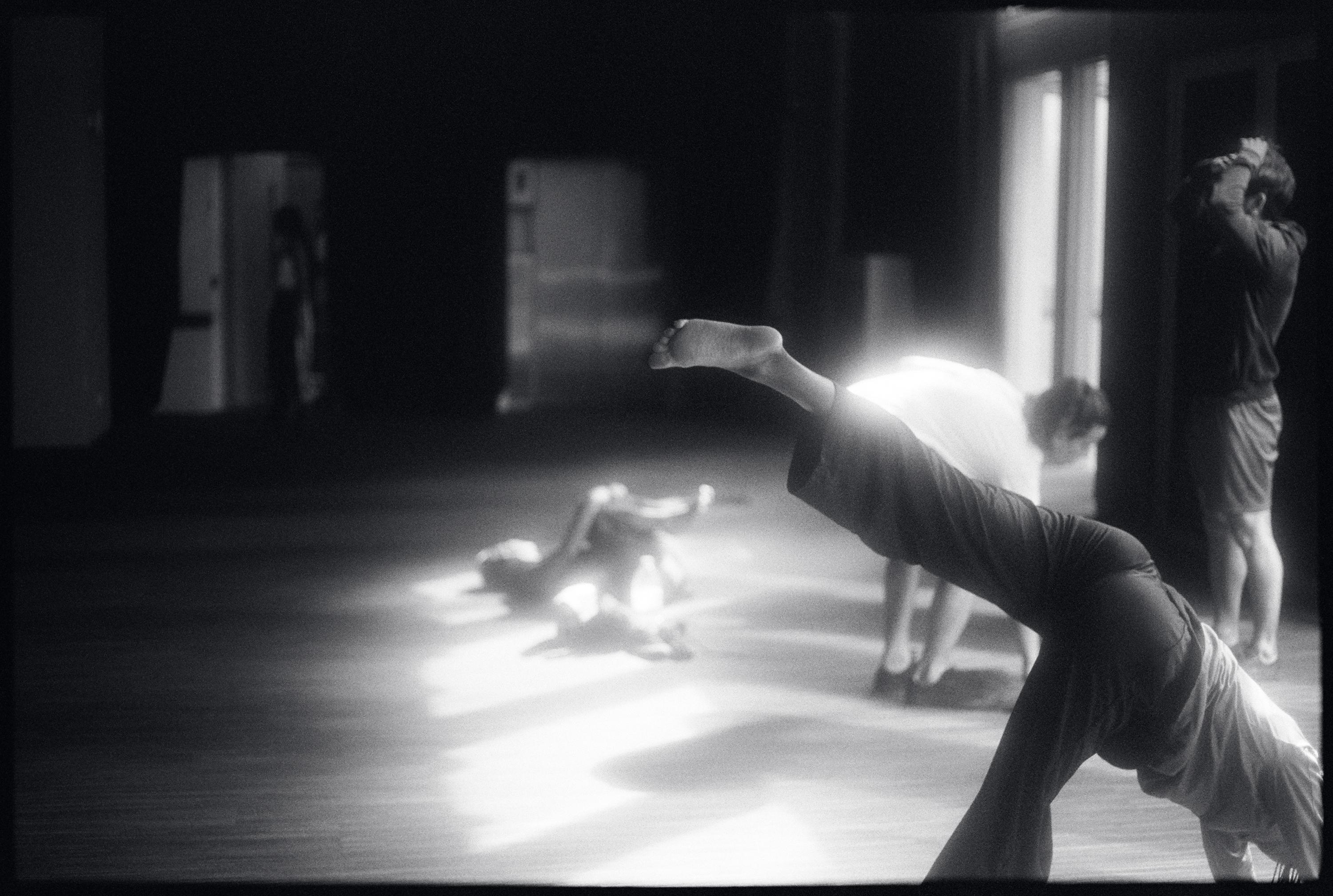

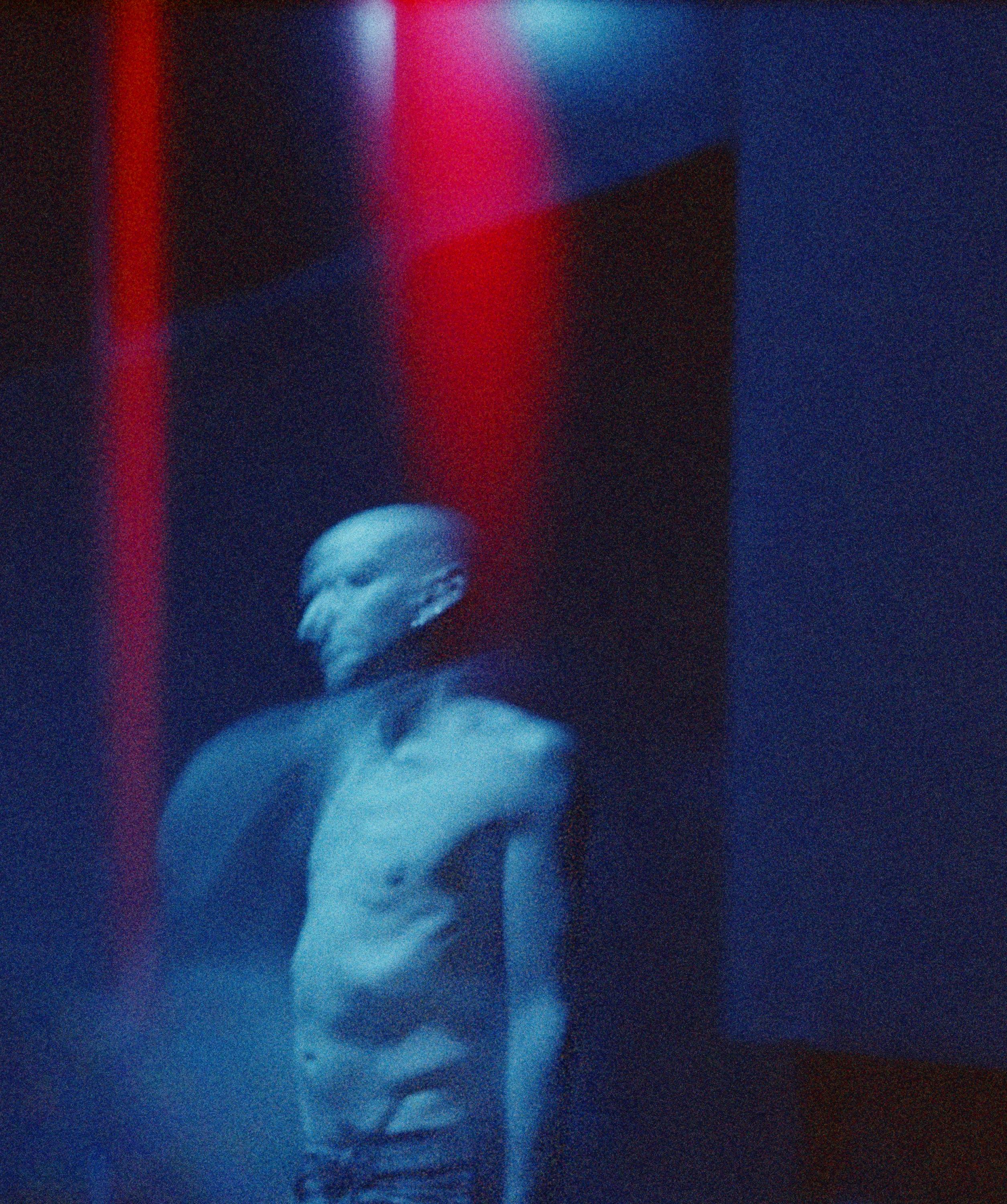

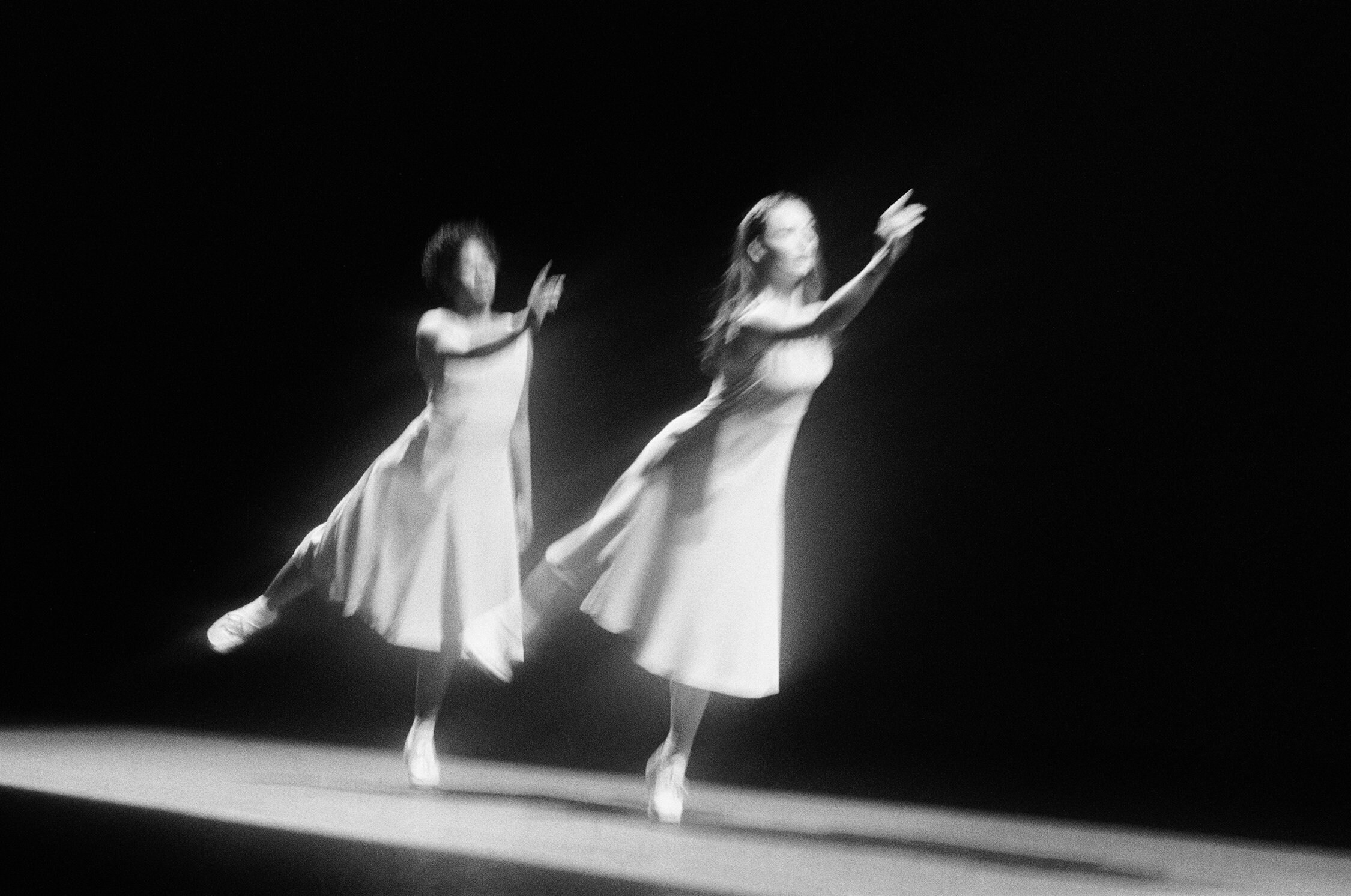

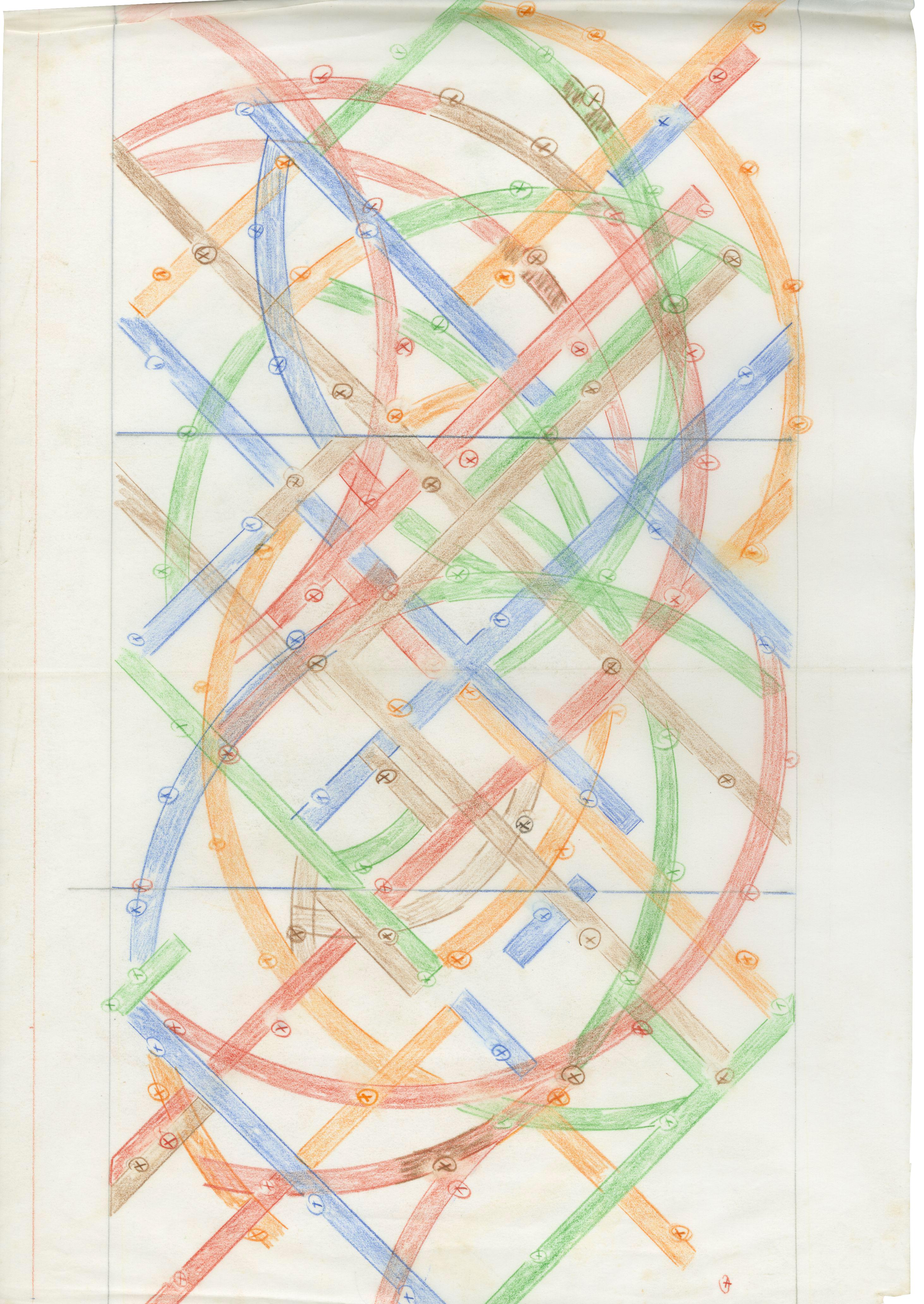

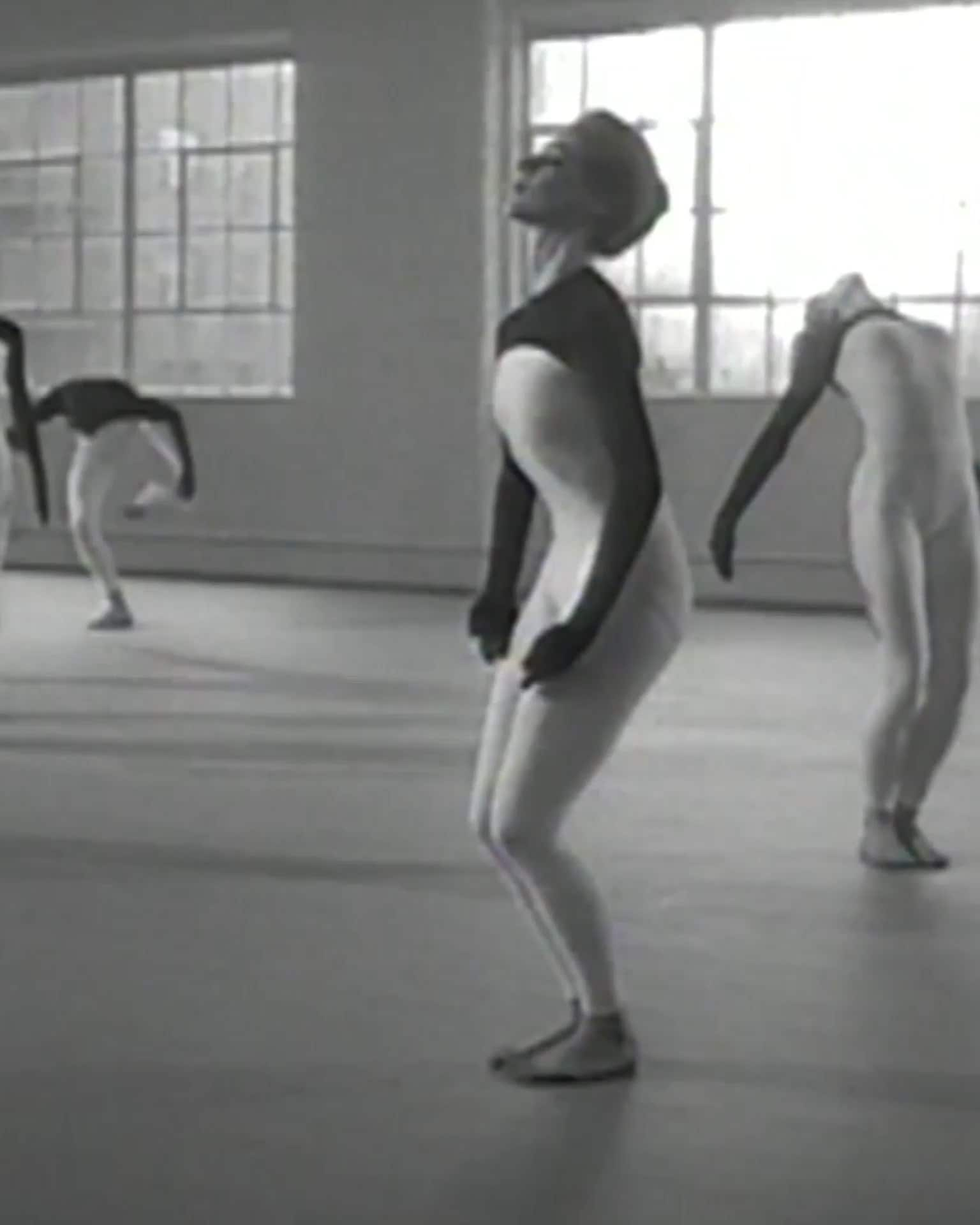

American photographer Olivia Bee lives a life of movement. Based on a farm in rural Oregon, she also travels the world for luxury fashion shoots. Since 2022, she’s been documenting the annual festival Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels in London, Hong Kong, and New York. This fall, her exhibition I felt the stars in that room will be part of the 2024 festival in Kyoto. Much like Bee, this conversation weaves between dance, photography, and the magic of the uncertain.

Dance seems to be a recurrent theme in your work but your previous series, Ballet, conveys a whole different atmosphere from I felt the stars in that room. Was this project a lot different from what you usually do?

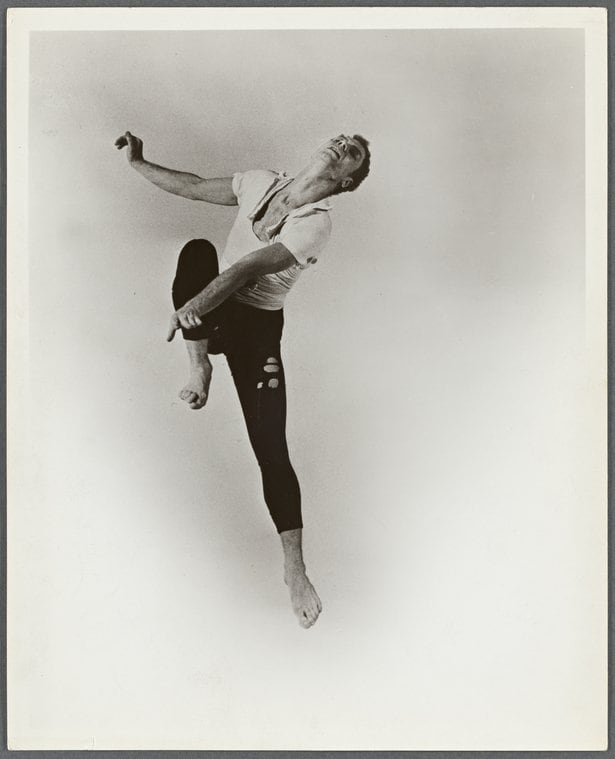

Olivia Bee: I think the differences have more to do with the respective aesthetics of modern and classical dance. In Ballet, I followed the company dancers of the American Ballet Theater. In that universe, even the stolen moments instantly come across as very staged, which is less the case with modern dancers in street clothes. But both projects were really just about going into the mind of the dancers and finding what dance feels like, how it can transport you in an almost visceral way.

All your work shows a very peculiar way of capturing movement and gesture, as if this visceral moment you’re talking about was something you’re living from within. Do you have a dance practice yourself?

O. B.: I really wouldn’t call myself a dancer, but when I did the Ballet project I took some beginner ballet classes to understand how it felt. I’ve loved dance my whole life and have been fascinated with, in ballet particularly, the search for perfection and how you never really get there but you keep striving for it. As for gestures, I think I’ve always been interested in those small moments that connect people, and how something that seems at first glance insignificant becomes extraordinary when you’re giving it attention. Shooting dancers doing their thing wasn’t any different from that. There is something already very picturesque about the way they’re moving.

Your work creates a point of tension in between something very instantaneous and a composed, almost painting-like quality. Are you usually capturing the moments or sometimes staging them?

O. B.: I really love painting, especially from the 17th and 18th century. I love the way light is treated in it and how it manages to show the little prosaic things as if they were the most important things ever. And that is what I try to bring in my photography: showing the spontaneous moments in a gold frame. I really try to walk the line between documentary and a sort of dreamy portraiture, and it has to be a really nice combination of both for me to like it. Sometimes I set up portraits and have people do something but most of the pictures from the I felt the stars in that room series were just taken as things were happening.

You shoot mostly analog photography, right? Is there a specific reason for that?

O. B.: Yes, this series is all analog. I think shooting film enables me to really be in my artist flow state. With analog you can’t see the picture instantly, so you have to have this feeling inside of ‘ok we got it,’ instead of already being in the post-production mindset and looking too much at your images. And I like that the mistakes that you make in analog photography are often very beautiful; if a roll comes back slightly scratched, I’m happy. One of my favorite photographers is Sally Mann and she calls it “the angel of uncertainty.” She always hopes that something strange will come up. I think that is very prevalent when you have a tactile media.

Talking about Sally Mann, your work conveys a similar atmosphere, tainted with the Americana and Southern Gothic aesthetics. For the first one, a style that is representative and even stereotypical of American culture, and for the second, a form of dark romanticism inspired by the rural and poor South of the post Civil War Era. Is this part of your references?

O. B.: It is, absolutely. The US is a weird place because we have such a small and flawed history, especially on the West Coast, and this imaginary is the closest we have to a collective folklore. I’m very keen on showing anything that is iconic, or even cliché, and unveiling the humanity and the emotions behind it. And, again, I’m always looking for those painterly moments that are quite timeless and universal; I want people to look at a picture and wonder if this scene is from 1850 or from last week. I’m living on a farm now, and it’s gotten me even more interested in the universe of women in the West and agriculture. When I take a step back from what I do every day, I really want to take pictures of it. To me, photography is really about capturing the moments that make life beautiful and worth it. There could be this sunset light and I’m wearing a dress, or my husband is coated in oil and grease from working on his truck all day, and you know it captures something about our existence here, in its most ethereal and magical aspect.

Interview by Lena Hervé

A multifaceted artist, Lena Hervé first trained as a photographer before experimenting with performance and sound practices. Since 2021, she has been a regular contributor to the multidisciplinary cultural magazine Mouvement.

I felt the stars in that room

Exhibition

Photographer: Olivia Bee

from October 4 to November 16, 2024 during the Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels Festival, Kyoto, Japon