Was choreographic writing unthinkable for you at the time?

Christian Rizzo: There was definitely a certain type of nonsense, that’s for sure. On the other hand, there was a notion, at the same time a desire, which came by doing, and that was key — the question of movement. And it was not the prerogative of the body to take charge of 100 percent of the question of movement; all the elements interested me, in fact — whether it is a question of the object, of a light, of a sound, of the spatiality, etc… all were trending towards the notion of choreography, since the objects that emerged from these experiences became forms by themselves. And I felt that it had to do with dance — but there wasn't any dance. So, I believe that the idea of the word "choreographic" took a long time to appear, because, for a long time, I said that they were "propositions." I called them "propositions," and, later on, the word "choreography" also came into play. I no longer signed propositions, but choreographies instead, since I didn’t really know what it was myself, except that I felt that there was the notion of sharing the movement, or of taking over the movement, by several referential elements, including the body, when there was one, or not, when there was none. But that something was woven and appeared in the establishment of a relationship between my objects of work.

What led you to adopt the term choreography to describe your work?

CR: It's very much related to my background, since I once had a lot of trouble thinking of myself as a dancer. I think the imagery I had of the dancer was an imagery, even before I was deep into the practice, that was beyond me. I would say that it was really shaky for a very long time, even when I was asked what I was doing: I would say that I work in dance or I would avoid the question of already calling myself a dancer, ‘cause I got in through back doors, one might say, in a roundabout way. So, it was a "proposition" for me — I did not really know what I was sharing between myself and the other. I knew that I had a need to produce forms in which the question of movement was central, but I didn't know which discipline it belonged to. In fact, I didn't know if it was ultimately a kind of rock music, but which took another form; was it a music-related matter, but which morphed into something other than a concert, or something like that? They were not installations either, because they had a beginning and an end. So, they still required spectacular attention, with a dramaturgy inside. I think I was a bit like Humpty Dumpty, greatly unbalanced. So, I didn't want to risk, at a given moment, attributing these forms to a certain field that would automatically demand a certain perspective on the proposed objects. So, I deliberately left it very open-ended, because I was myself, I think, was into doing and intuition, and I think this intuition demanded that I not be named. So, in the end, I was proposing things, and I couldn't even say at what point the word "choreography" came up. I didn't look into that, but it would be interesting to see. Is there a piece at any point that highlights that? Everyone works with the body, so it was a lot of work on immobility, on posture. And I believe that, at a given moment, these postures were put in movement, that they posed the question of movement or perhaps the spatiality of the postures even more. I think I started seeing what I was doing no longer in terms of working on planes or perspectives, but rather with a view of the image. If we shorten it: to look through the flow, in fact. I believe that, at that point, I began to see things appear. Maybe that's when I told myself this is choreography.

How do you develop the writing of a piece today, when you come into the studio with the dancers?

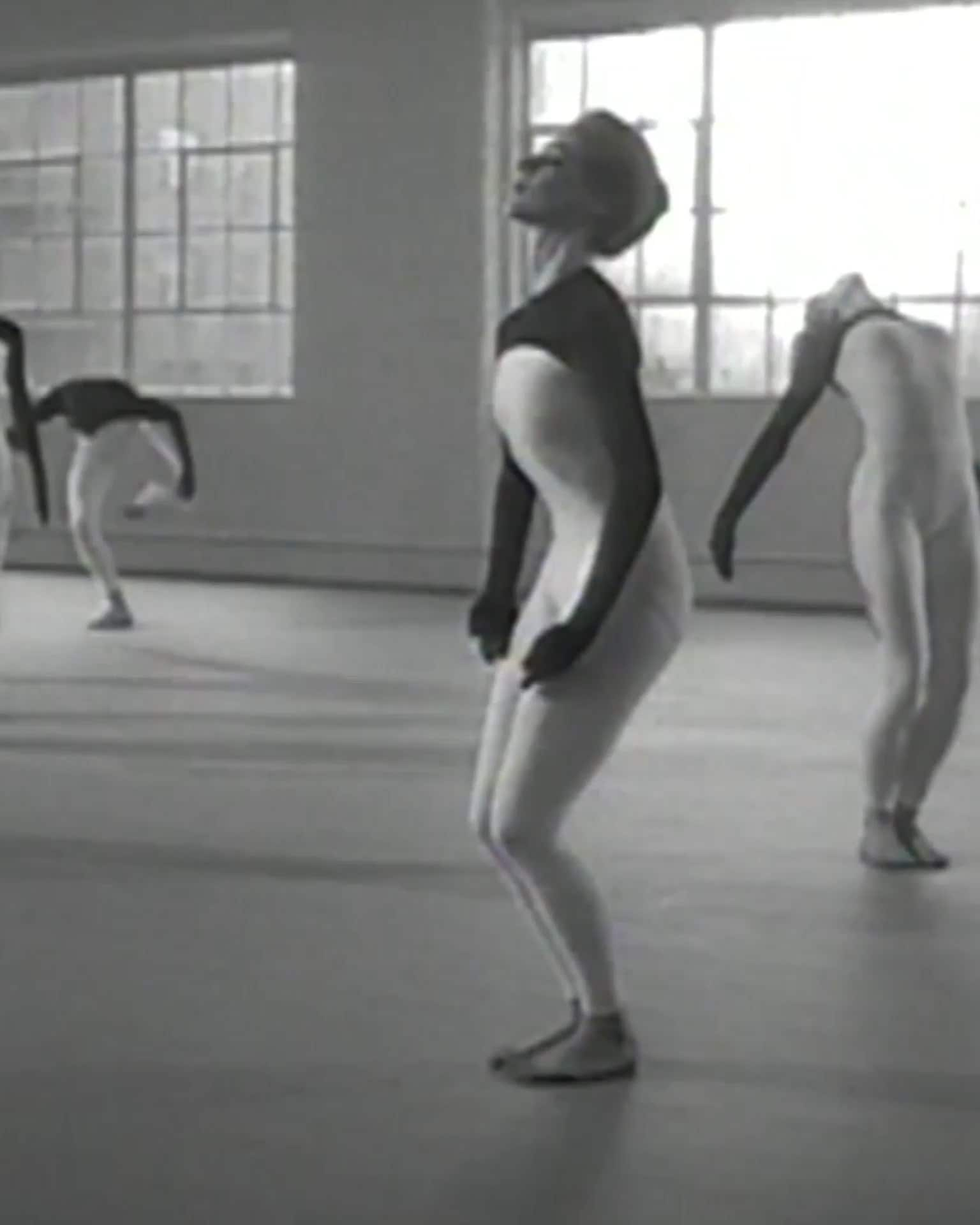

CR: Once the dancers are there, we work on a lot in improvisation from protocols, until it forms a musicality but also a spatial musicality — a form of musicality or patterns, not by the ears but by the eye — which seems to me to meet something which is still vague in my head, but which seems to resonate. So, I say to myself, I don't know what it is, but it informs this fuzzy area that is the start of the project. And so, I quickly set up some building blocks. Once they are set, I intervene again, meaning I recompose these movements, these flows which are still almost only matter. However, it is matter that is fixed, but I need to set it in order to be able to attack it with a hammer and chisel, almost like a sculptor. In other words, to bring out what is inside this form, almost its skeleton at first, by digging a lot, in the negative, until a form of musical score appears — and this is very subjective — and it seems to me to be right, which informs this specific project all at once. It is also to understand how each body, in its understanding of what I can tell, will translate these intentions. And then, things spring up that, frankly, I couldn’t make spring up myself. I work with ghosts, with very blurred forms, but as soon as they are incarnated, it sometimes brings them totally elsewhere and outside the project. But sometimes it takes them to places that I simply could never have imagined. It only appears through these people, in this space, through these protocols. It's almost a collective intelligence that brings out a composition. I always have the image of an octopus with eight brains. With each brain like that, and that everyone thinks together, in movement. This formulates a spatial thought that I could never direct, or even think alone. It would be inconceivable in fact. So, as I was saying earlier, as soon as these forms of scores appear, I can see them again and try to see what is missing, what is too much. For me, composing or writing is like cooking, in the sense that once you have these ingredients, you have to be at the stove, and you have to taste all the time. It's not "we put this in and wait twelve minutes," and then it's finished. There's this thing to taste, until a given moment when you feel that a form of balance has been reached. You need to put out the fire, stop. We say, “That's it, we don't touch it anymore, it's good, we must serve it.” I talk a lot about cooking because I am someone who cooks a lot, and I like it a lot. But, for me, it's a close counterpart to collecting materials, trying to coexist and see how you can taste each food for what it is and, at the same time, that the common composition can bring out a common taste. It's always this kind of in-between, but it's always through exploration.

What was the genesis of En son lieu, a solo created during the pandemic and presented at CN D in June as part of "Camping?"

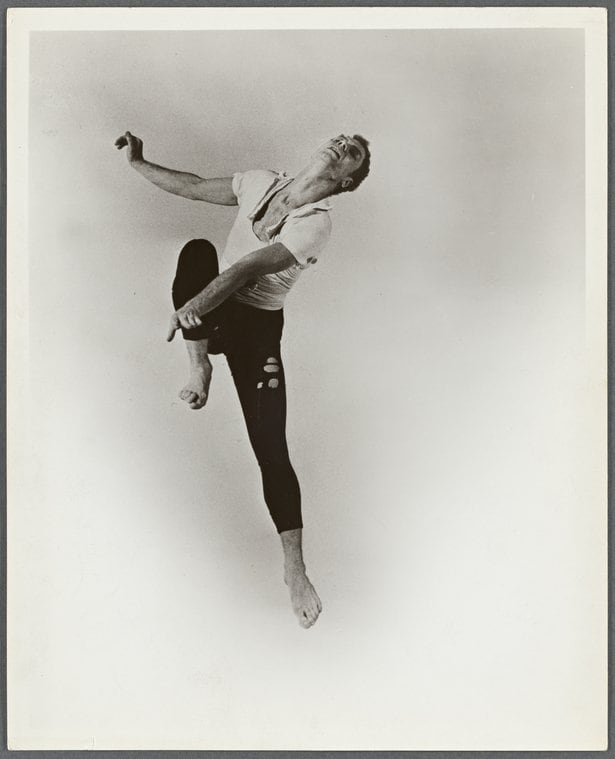

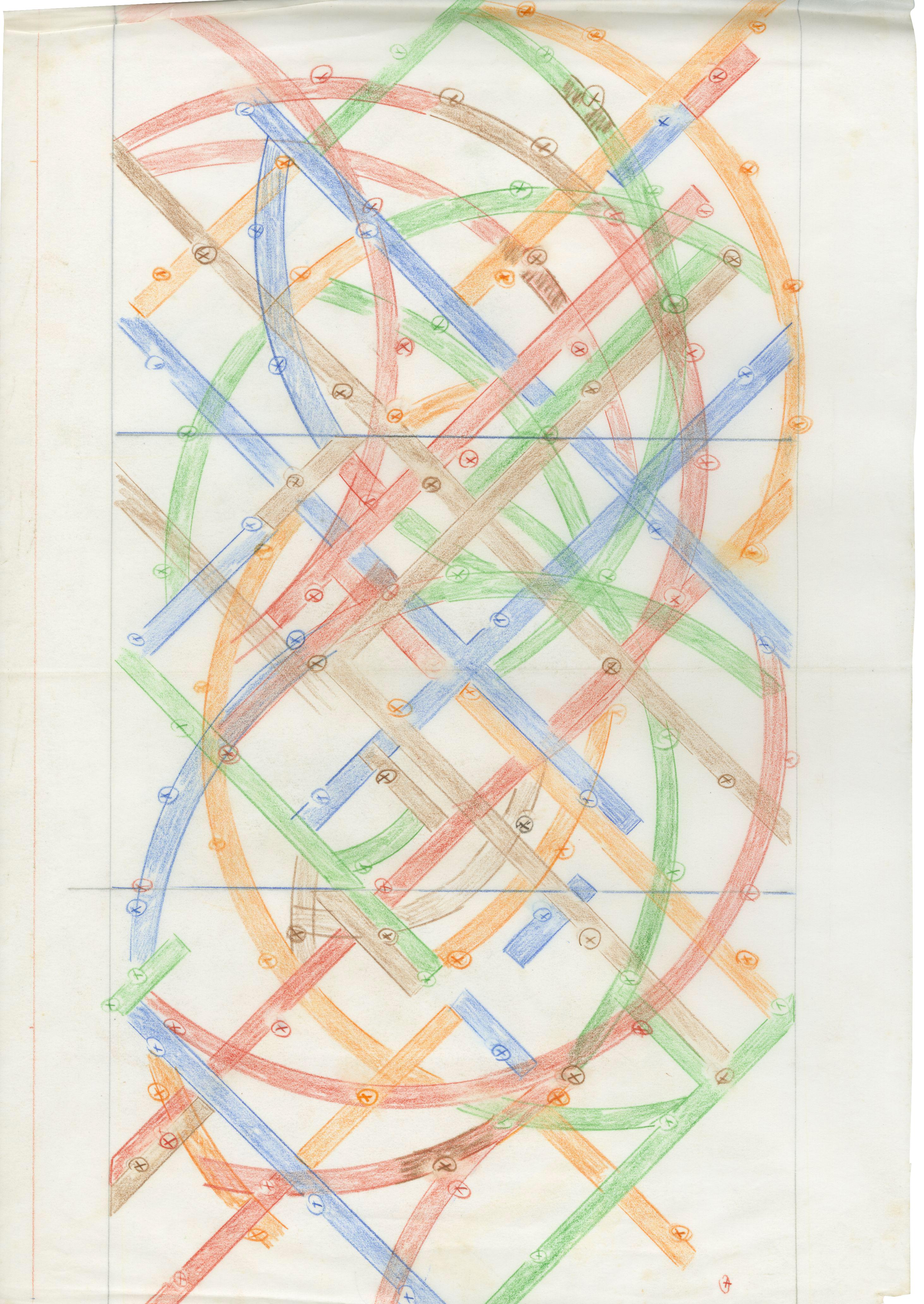

CR: For En son lieu, the solo for Nicolas Fayol, what is quite comical is that it is exactly the opposite of what I was talking about. The process was totally different, because we started during the lockdown. I absolutely wanted to try to work during that time because we were already so far behind. So, we worked remotely. I was, by chance, in the middle of the mountains, and Nicolas lives in the countryside, near Salagou lake. And so, I said: “Can't we try to get something started so we don't have to wait for our launch?” So, I started writing protocols. I invented all kinds of protocols, drawings, writings, rebuses, things like that. And I said to him: “I send you this, you interpret it, choose outdoor spaces and try to translate these protocols into dance, to associate them with outdoor spaces. You film yourself; you send me the video and then in the evening we debrief, etc.” I was throwing myself into something because I really wanted us to put something in place. And it turns out that we did that for a week. And so, two protocols per day, two videos per day, in the evening we check, we discuss, jump to two new protocols for the next day, and we finally found ourselves working in a totally different way because there were written things, sometimes quite incomprehensible. For example, drawings of steps that I had made: A walking part that I tried to redraw with my eyes closed and there you go, that's your path. Finally, how can we interpret a language that is totally foreign to us and still consider it as a score to be deciphered? It took many forms and spurted out many materials. And we stopped there, we said to ourselves, very well, the experience was great — it was even beyond great — it was very beautiful, because I had the impression of having a loving conversation, of writing and receiving answers every day. And we were able to reopen, we met again in the studio, and I asked her to come and bring the memory of this correspondence to the set. So, what was there? An empty set. And there it was, a kind of material sprang up, but with a line on the memory. I said to myself that it is very beautiful to try to do at the same time, to revive something that is not there. So how do we do it? One tries to put one's body back into movement and to place it in the present, always with the constant intent that this presence only constitutes a call to something that is not there, and it stops there. And then? And that is directly linked to the specificity of En son lieu and of Nicolas especially. What interested me is that Nicolas is experienced in the technique of break dancing, and we have always considered that break dancing was an urban dance, whereas Nicolas is someone who lives in the country, who was born in the country, and who learned break dancing in the country. As I like very much to have paradoxes in the work, namely to put together two things which apparently cannot coexist — since that’s where the stakes of choreography begin — I said to him: "Listen, I would love it if we could go to the forest or the mountains, to spaces that are really not practicable for break dancing, and see how your practice can survive these spaces, how it can be modified or what modification is needed so you still have the impression of break dancing, even though the conditions are not met.” In the end, this practice, which can be considered quite spectacular, or at least very outward-looking, turned out to be an extremely intimate practice, since the notion of fragility came about, quite simply by the surrounding space.

Photo : © DR