The glass ceiling has a way of enduring. Reine Prat wrote two reports on gender inequality in the performing arts for the French Ministry of Culture in 2006 and 2009, and she continues to expose its long-term effects: in 2021, she released her book Exploser le Plafond. Précis de féminisme à l’usage du monde de la culture (Rue de l’échiquier). In the wake of a new report from the ACCN (Association of National Choreographic Centers), which points out the declining number of women at the helm of France’s network of publicly funded dance centers, Prat delves into the underlying factors.

At the origins of modern dance, there were women – superb dancers who pioneered the emancipation of bodies, souls, and aesthetics: Loïe Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Martha Graham. Then came Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Pina Bausch, Yvonne Rainer. Women seemed to have found the space they deserved in the dance world. In the early 2000s, their brave and combative younger sisters – Mathilde Monnier, Odile Duboc, Régine Chopinot, Maguy Marin and many others – held 43 % of director positions in France’s National Choreographic Centers (CCNs), while there were only three female theater directors at the helm of National Dramatic Centers.

Had dance broken free from its patriarchal shackles, whose stifling grip remains obvious in the arts world? Had female dancers and choreographers been preserved from the systemic illegitimacy applied to any woman who dares to speak out and act for herself? The illusion no longer holds: on January 1st, 2023, their numbers had dwindled to the point that only three National Choreographic Centers were directed by women, whose presence on French stages is increasingly drowned out by male artists (even though this phenomenon is difficult to quantify). And still, we’re told: “Things are moving forward in spite of it all!” NO. There are windows that open, then the shutters bang shut, abruptly. Ignoring the legacy of dance’s pioneers, too many dance schools continue to draw in hundreds of little girls who are either white and blonde, or wish to be. The traditional outfit they don – the tutu, ballet shoes and tight bun – prepares them to be performers at best. These little girls’ desires are constructed by public policies, by the large retailers that sell them pink items with the help of some complicit parents. If they give up dance, the thinking goes, at least they’ll have gotten some poise and grace out of it. For the ones who aspire to become choreographers, the ACCN’s recent investigation shows very well how the system is rigged against them. One example: while the three female artists at the helm of CCNs account for 16 % of all CCN directors, they are only allocated 8.7 % of the funding for the entire network.

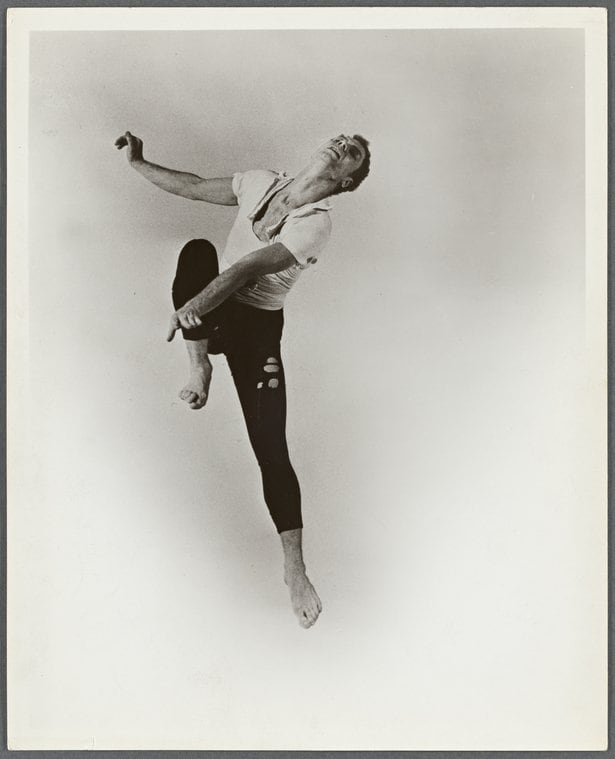

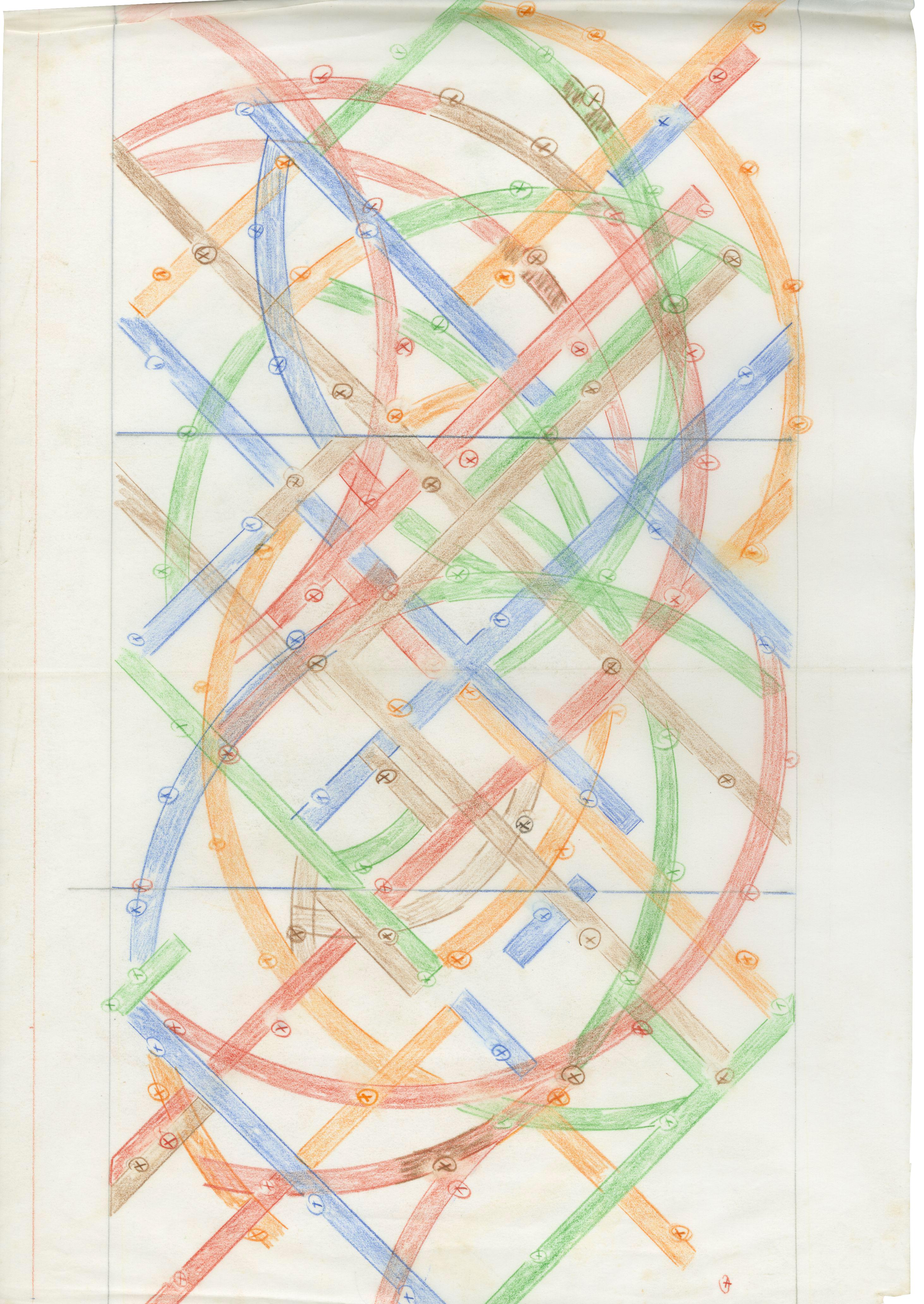

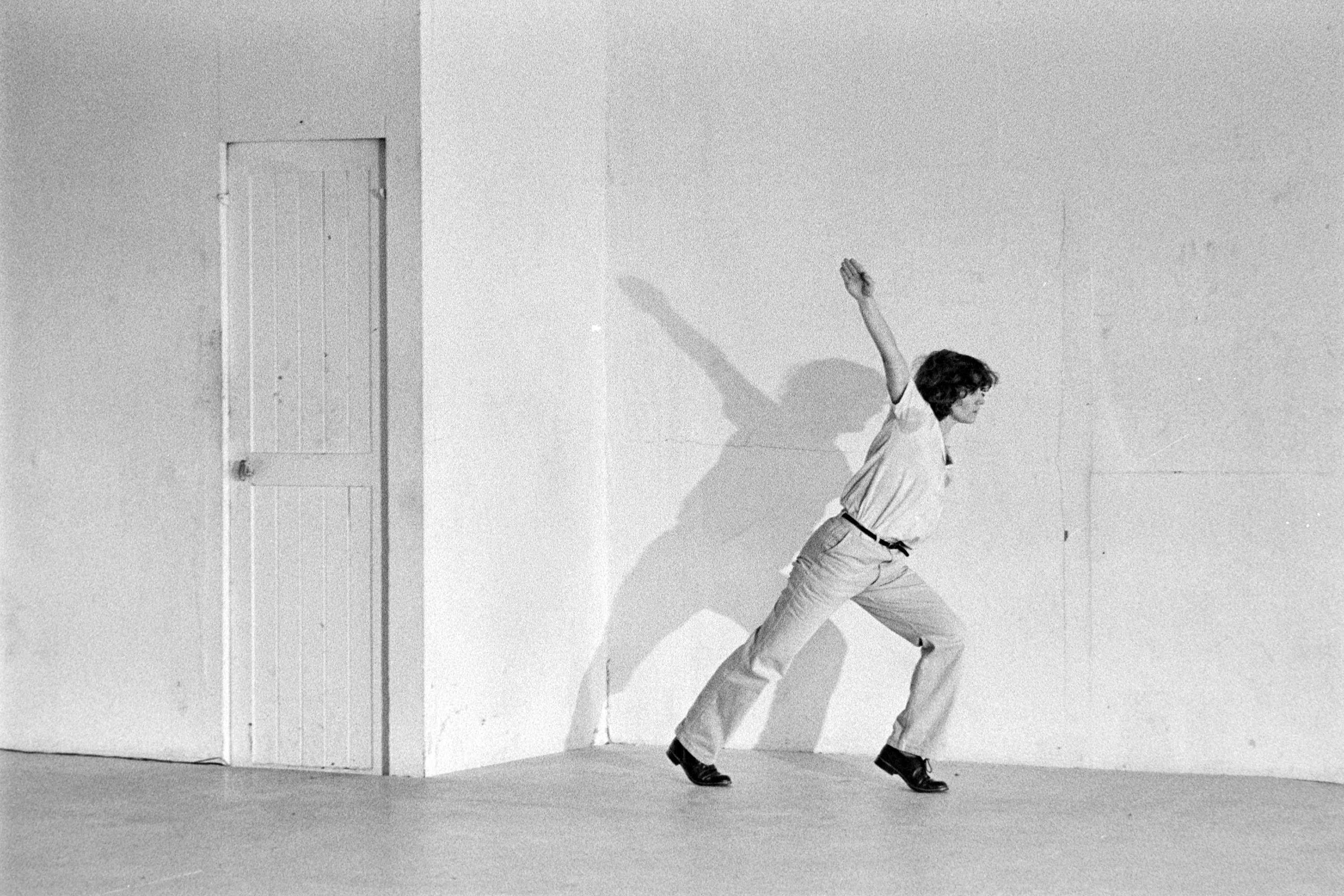

© Maguy Marin © Médiathèque du CND-Fonds Jean-Marie Gourreau

© Maguy Marin © Médiathèque du CND-Fonds Jean-Marie Gourreau

Women have been active in all artforms, and all fields of science. They have often been paved the way for technological discoveries, up until the moment when their field began to gain attention and become attractive, symbolically and financially. When there were suddenly positions and seats to fill, they were relegated to folding seats. This is the same old story: women were also kicked out of medicine, which they’d practiced until the Renaissance, and more recently, they’ve been forced to remain in front of the camera, and evicted from now-lucrative computer science jobs.

They still had dance: if people once doubted women had a soul, the fact that they had a body – to which they’ve often been reduced – was never questioned. Dance, therefore, was a suitable career for them, especially since female choreographers worked with their own bodies. Isadora Duncan’s dance is rooted in her body. Neither she nor Loïe Fuller spoke of themselves as choreographers, they were dancers, which is at least better than the notion that they interpreted something – a term that dials down an artist’s creative role, and is rarely used when a male director gives their interpretation of a play (in this case, they’re an author). Dance has also long been treated like a minor art by the Ministry of Culture, and placed under the tutelage of the powerful Music Department. With the creation of the National Choreographic Center label in 1984, and then of the Dance Delegation in 1987, contemporary dance was finally granted entry into the institutions. The field became attractive as it was given public funding, attention and institutional power – and consequently men started to dominate it, inevitably.

With one notable specificity, it seems: did the advent of new dance forms, like non-dance or hip-hop, accelerate this evolution? The way public policies embraced diversity has meant that more men have become involved: to this day, none of the female dancers that were pioneers in hip-hop’s transition from street to stage have been appointed at the helm of a National Choreographic Center. It’s only one example: An in-depth study would be welcome to evaluate the gender biases and more generally, the racial and class biases that are connected to aesthetic choices and the way critical and institution attention is allotted.

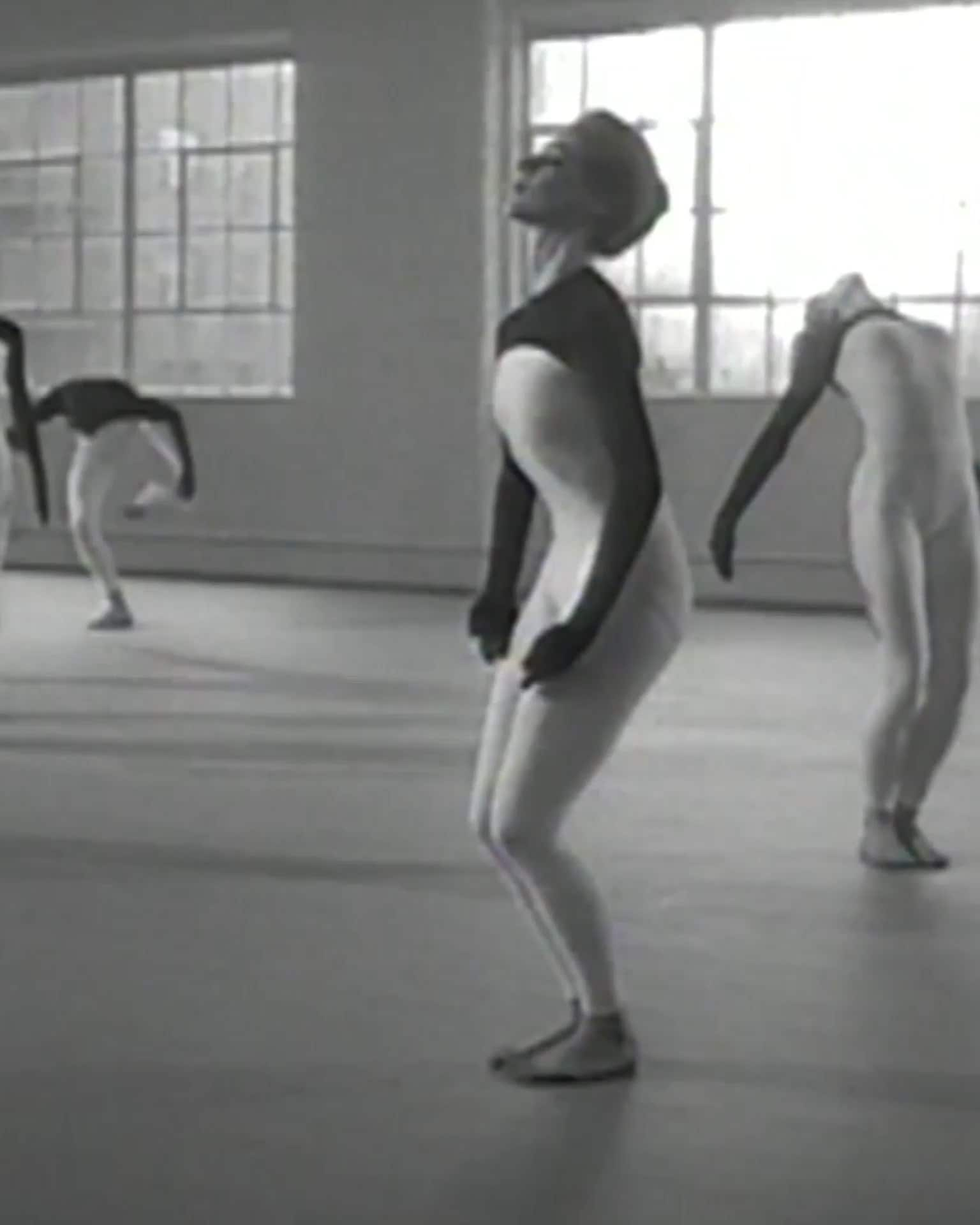

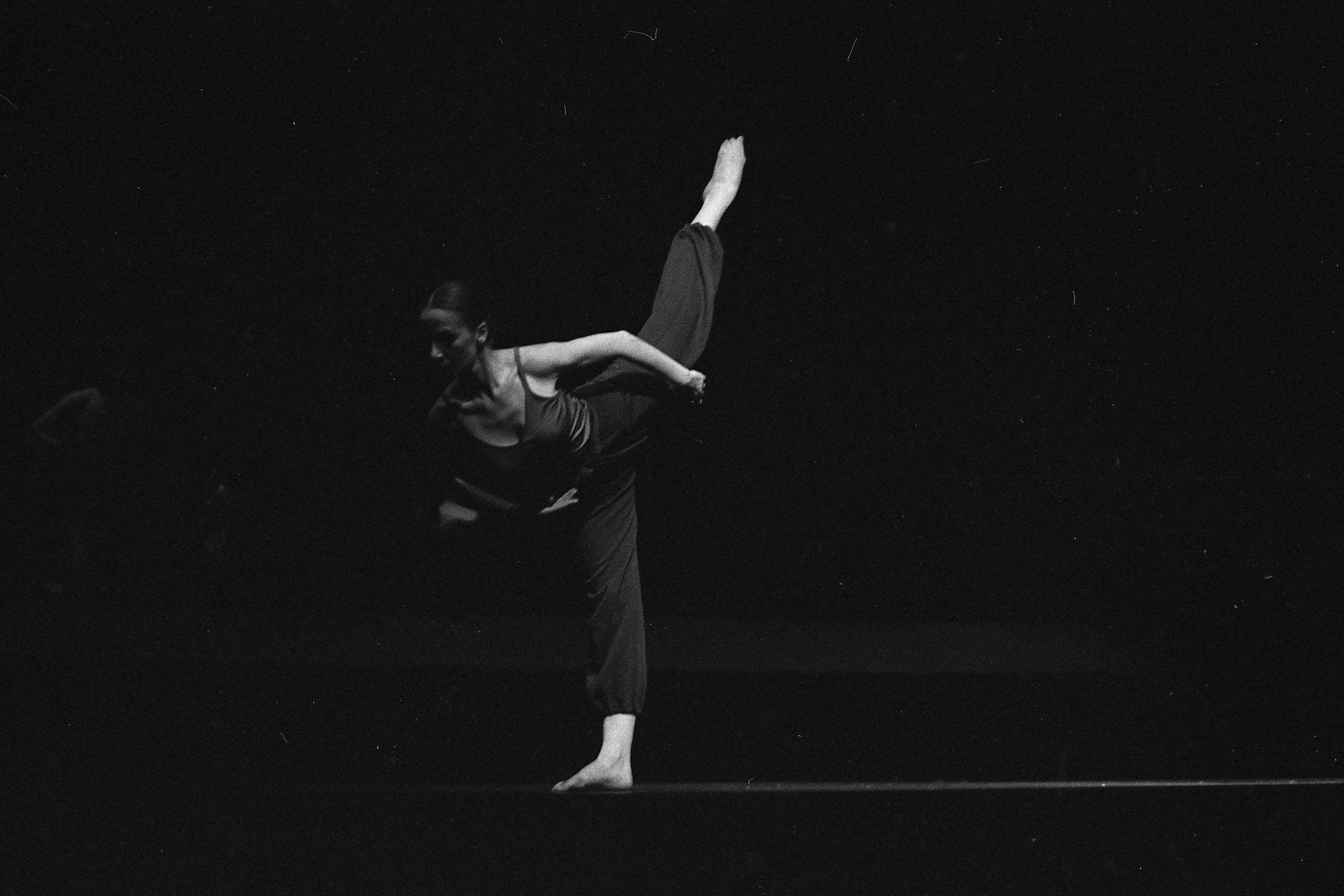

© Odile Duboc © Médiathèque du CND-Fonds Claudio Rey

© Odile Duboc © Médiathèque du CND-Fonds Claudio Rey

While dance had a head start, and the phasing out of female choreographers at this level is happening against the grain in the art world, the pattern remains the same: ever the pioneers, never legitimate.

Shall we leave the conclusion to Charles Pasqua, who in the mid-1990s told France’s National Assembly: “Of course no one here is going to say they’re opposed to having more women in the public sphere! But if we were to ask how many of you are willing to resign to leave their seat to a woman, how many of you would say yes? So […] let’s be a little less hypocritical!”

To do better, let’s collectively devise means to enact the recommendations of the ACCN and measure their effects, without delay.

Infos

ACCN

accn.fr

Ministerial reports on equal access for women and men to positions of responsibility, decision-making positions, production resources, distribution networks and media visibility.

↷ Mission ÉgalitéS (FR)

↷ De l'interdit à l'empêchement (FR)

Photo : © Jean-Marie Goureau