The opening and closing ceremonies of the Olympic and Paralympic Games are highly anticipated shows of titanic proportions, featuring the arrival of various officials, anthems, a parade of flags and athletes, artistic performances, and grandiose scenography. In Paris, Thomas Jolly was named artistic director, and he turned to choreographers Maud Le Pladec and Alexander Ekman for the dance sequences. Although dance will be a mainstay of the celebrations, in the past its place has not always been guaranteed and its role sometimes misappropriated.

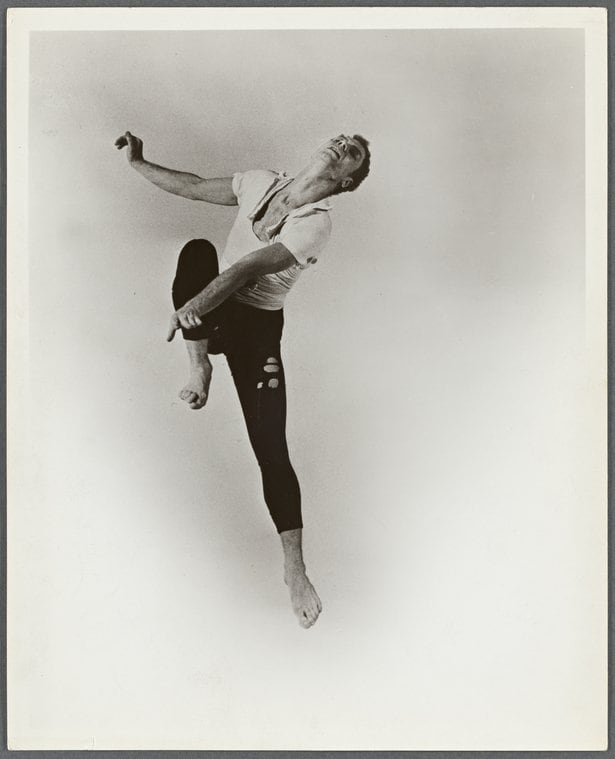

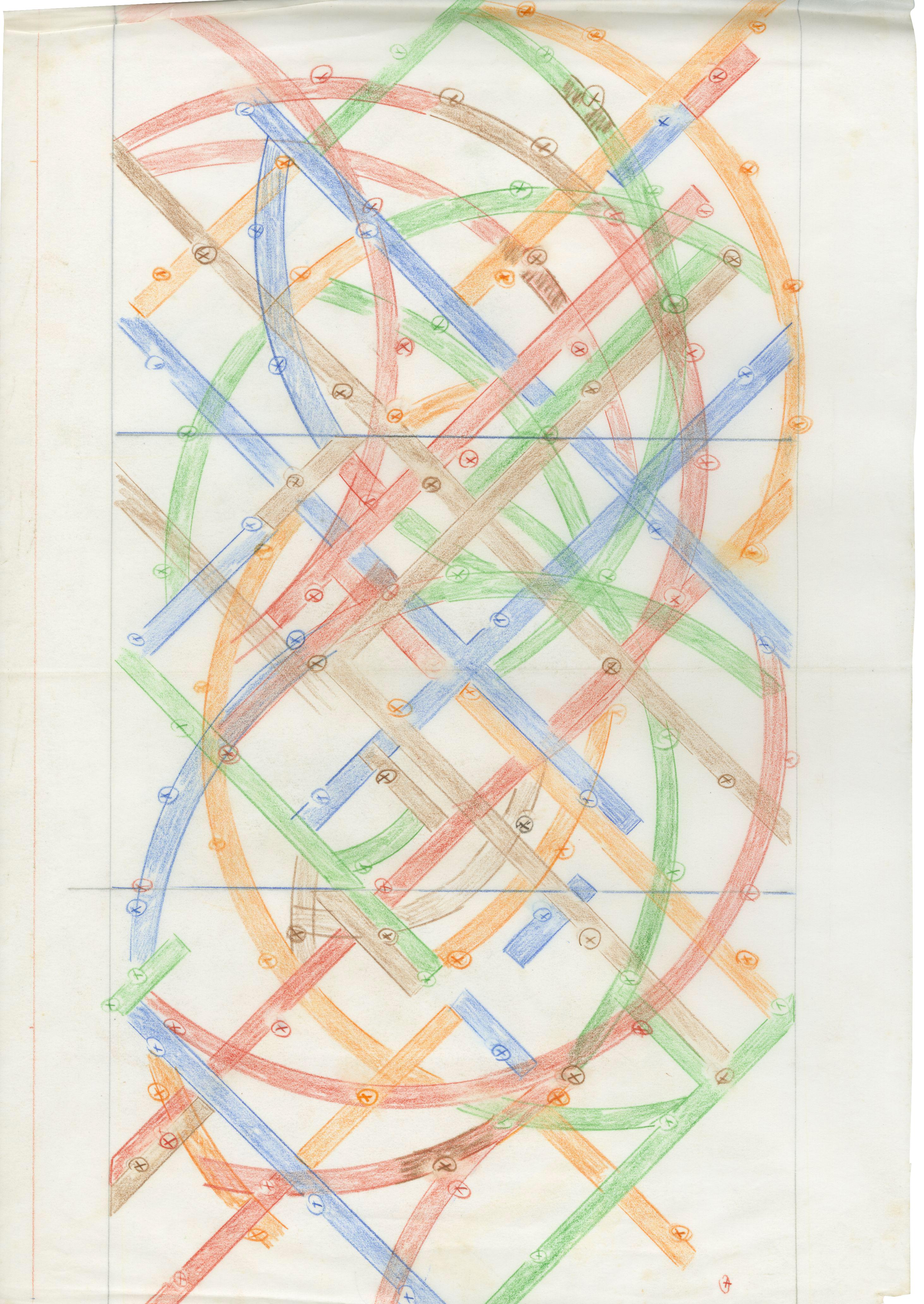

“I remember being granted a lot of freedom… The idea was to highlight youth and sports,” recalls Philippe Decouflé. “It had to be visually striking.” In 1992, the French artist choreographed the opening ceremony of the Albertville Winter Olympics, and hit the nail on the head. His show proved to be quite avant-garde, tinged with futurism and magic. Decouflé combined circus performances – with acrobats on elastic bands and stilt-walkers transformed into snowflakes – theater, and contemporary dance, with skiers breaking down their technique and performers dressed in snowball outfits created by Philippe Guillotel.

The event mobilized 3,000 participants and included professional artists and amateur performers, for an on-site audience of 35,000 people and two billion television viewers, giving visibility to a type of contemporary dance that had, until then, mostly been limited to select performance venues. Above all, Decouflé’s 1992 spectacle set a precedent: the staging of the opening and closing ceremonies of the Olympic and Paralympic Games could no longer be imagined without including contemporary dance. Choreography, however, does not always have a leading role and is often used to serve a national narrative (intentionally or not), and its place in these unifying events is constantly being called into question.

© Costumes de microbe, de danseuse et de débouleuse par Philippe Guillotel, portés lors de la cérémonie d’ouverture des Jeux olympiques d’hiver, Albertville, 1992 / Coll. CNCS, dépôt de la Bibliothèque nationale de France © CNCS / Terminal 33

© Costumes de microbe, de danseuse et de débouleuse par Philippe Guillotel, portés lors de la cérémonie d’ouverture des Jeux olympiques d’hiver, Albertville, 1992 / Coll. CNCS, dépôt de la Bibliothèque nationale de France © CNCS / Terminal 33

“It was a great opportunity to be able to create a show of this magnitude,” says Decouflé. “I’d already taken part in major events, creating La Danse des sabots for the bicentenary of the French Revolution, directed by Jean-Paul Goude. I wasn’t totally unfamiliar with that type of challenge.” Thirty at the time of the 1992 winter Olympics, Decouflé was entrusted with the design of the entire ceremony. Inspired by the liveliness of musicals, the form of dance that fits TV broadcasting the best, the artist was well aware that he was shaking things up. He claims that, before his time, there wasn’t much “in terms of spectacle apart from formalities such as the parade of athletes and the presentation of flags, which are still part of the specifications.”

With his characteristic sense of whimsy, he conveyed to the world an image of France that was oriented towards creative innovation rather than tradition – even though a farandole by Savoyard dance groups paraded at the closing ceremony. “Decouflé revolutionized [Olympic] ceremonies. Before him, they were very folkloric, featuring large ensembles,” says Sylvain Bouchet, a historian specializing in the Olympic Games. The academic also points out that dance has not always been part of the festivities, even though art and spectacle are part of the DNA of the modern Olympics, launched in 1896. “Their initiator, Pierre de Coubertin, was fascinated by the processions of Greek and Roman Antiquity, in which he saw a certain elegance.” De Coubertin, explains Bouchet, was also “a keen stage director, as evidenced by his theoretical texts in which he mentions figures such as Loïe Fuller and Isadora Duncan.”

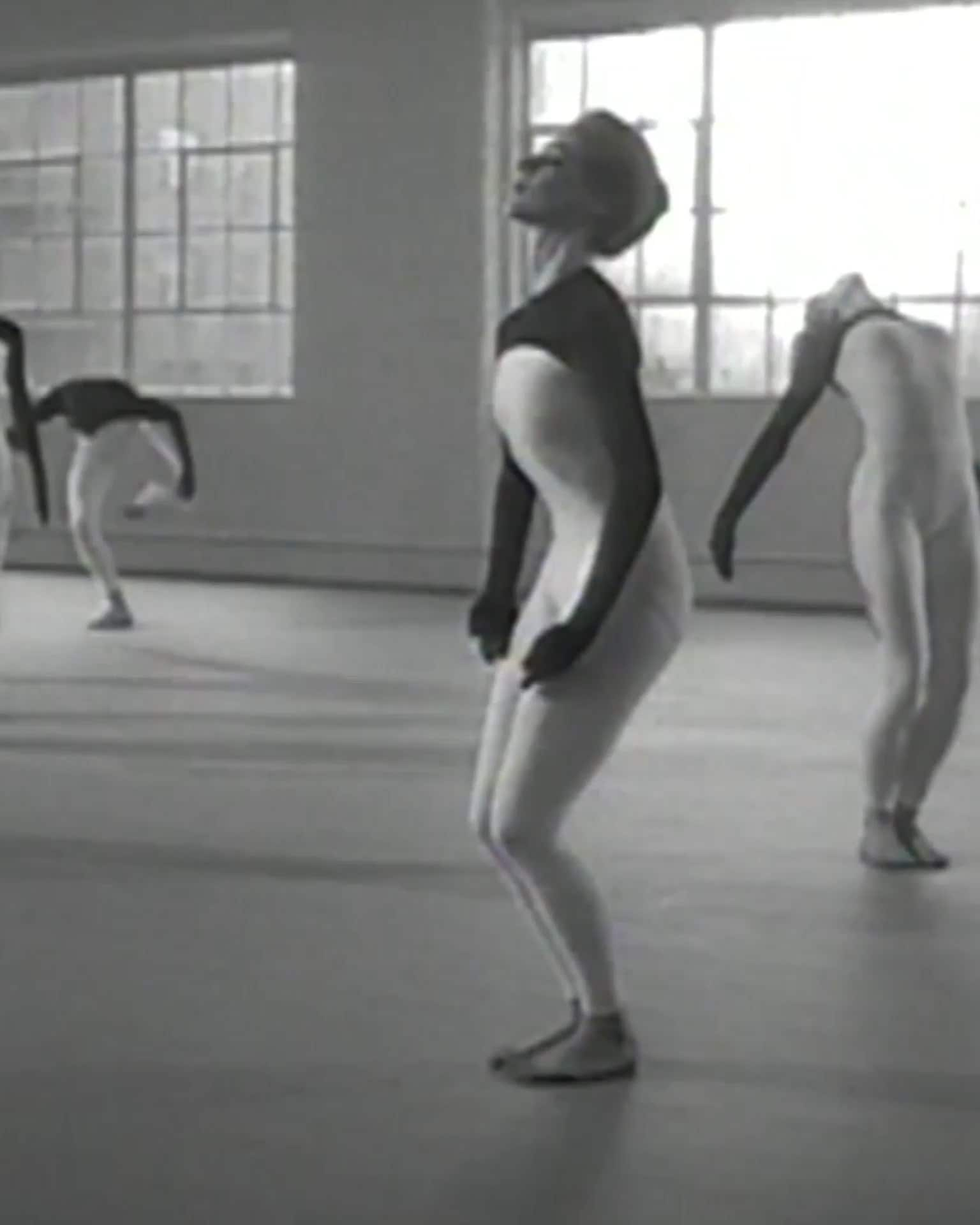

It wasn’t until forty years later that dance was really granted a place in the Olympic Games. “The infamous 1936 Berlin ceremony, under the Nazi regime, put this art form in the spotlight,” says Bouchet. “The dance represented a single body, in the same costume, performing the same movement to reproduce the ideology of the so-called Aryan race.” The leading choreographers of contemporary dance at the time, Rudolf Laban and Mary Wigman, were commissioned to create a piece for the occasion. But on the eve of the event, Laban’s performance was canceled by Joseph Goebbels, then the German Minister of Propaganda. “He wasn’t too keen on that type of modernity,” explains the historian.

© Capture d'écran du documentaire Les Jeux d’Hitler, Berlin 1936 de Jérôme Prieur (2016) © Roche Productions

© Capture d'écran du documentaire Les Jeux d’Hitler, Berlin 1936 de Jérôme Prieur (2016) © Roche Productions

The overtly partisan 1936 Olympic ceremony influenced all those that followed. For the commissioned artists, tackling such symbolic celebrations comes with an awareness of their political significance. In the 2000 Sydney ceremonies, the show retraced the constitution of Australian society and featured dances by Aboriginal performers, promoting multiculturalism. In Beijing in 2008, a national narrative materialized in traditional artistic forms and crowd movements with identical-seeming individuals, conveying a monoethnic image of Chinese society.

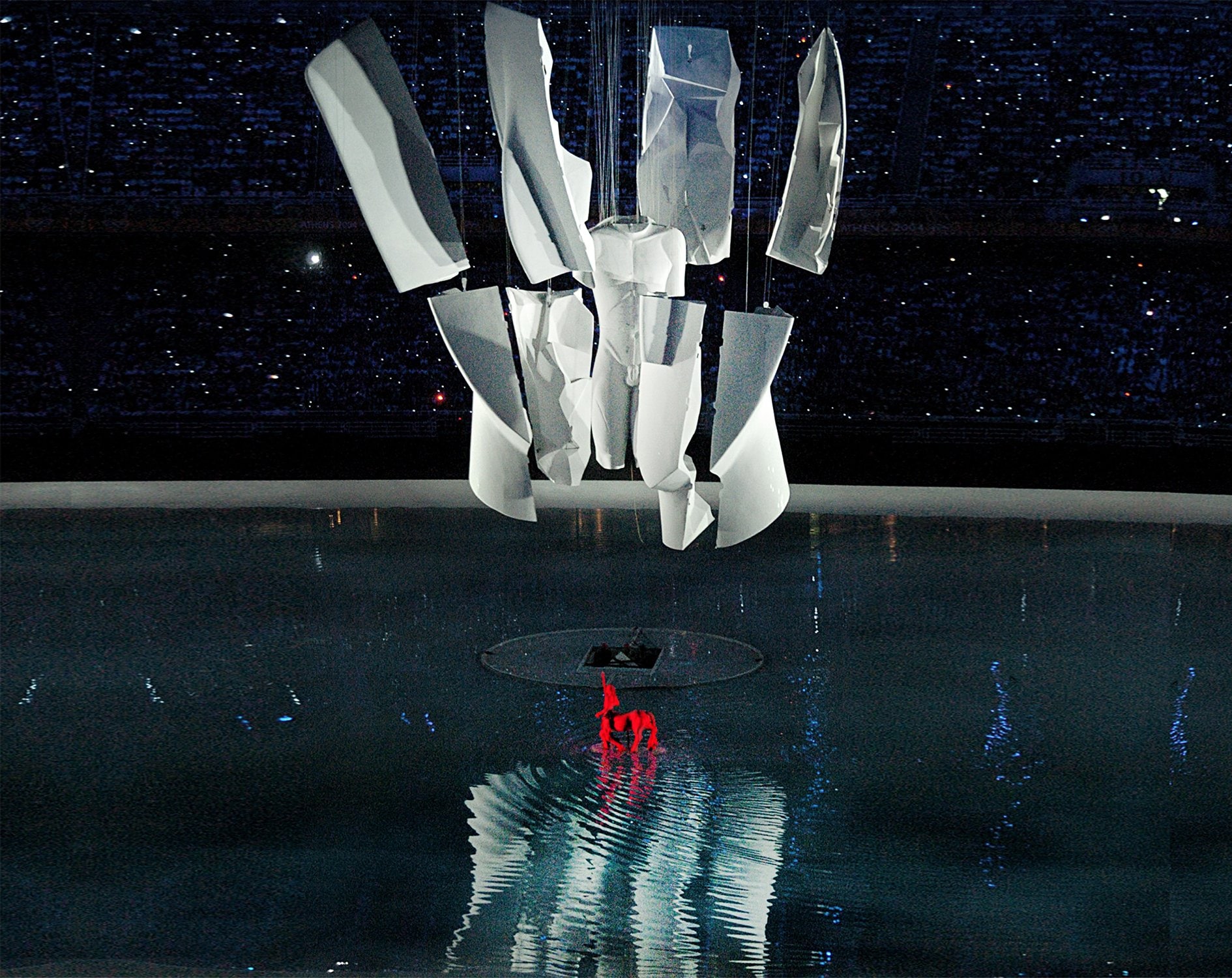

At the 2004 Games, Athens also turned towards the past. But the choreography, which took center stage, avoided the ideological pitfalls. Dimítris Papaïoánnou, who was chosen by the organizing committee, was an emerging artist at the time, known for his slow dances flirting with visual theater. His show unfurled a lively fresco that revisited the history of Greek art and, as a subtext, that of humanity itself. The Minoan snake goddess was featured, along with geometrically styled vases, caryatids, and enormous levitating sculptures. “I proposed a project that seemed totally impossible to me... And they said yes. The protocol is really very reasonable,” says the choreographer. “Looking back, I realize that I could have been even bolder!” Years later, people still remember the event and its artistic freedom. “This show made the Athenians proud,” says Papaïoánnou. “People still talk to me about it all the time.”

© BIRTHPLACE 2004 de Dimítris Papaïoánnou, directeur artistique des cérémonies des Jeux Olympiques d'Athènes en 2004 © Dimítris Papaïoánnou

© BIRTHPLACE 2004 de Dimítris Papaïoánnou, directeur artistique des cérémonies des Jeux Olympiques d'Athènes en 2004 © Dimítris Papaïoánnou

Although artists such as Akram Khan (London 2012) and Deborah Cokler (Rio 2016) have continued to prove contemporary dance an essential ingredient of Olympic ceremonies , Papaïoánnou and Decouflé have been the only choreographers to conceive the entire event. Despite their success, the trend in recent years has been to break away from dance. “The ceremonies are increasingly being entrusted to filmmakers. I think we’re heading for a reduction in the proportion of dance, at least in the very large compositions,” adds Bouchet, explaining that costs – including staff – are being reduced “thanks to video and new technologies.” With Thomas Jolly at the helm of the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games, alongside choreographers Maud Le Pladec and Alexander Ekman, will the ceremonies return to live performance? As the world’s biggest sporting event returns to France after 32 years, we can hope for a celebration in line with Decouflé’s visionary audacity.

Belinda Mathieu is a journalist and dance critic who works for several publications, including Télérama, Mouvement, Trois Couleurs, Sceneweb, and La Terrasse. She holds degrees in French literature (Université Paris-Sorbonne), journalism (ISCPA) and a BA in dance from Université Paris 8. She is currently enrolled in their MA program and she continues to reflect on her practice and what is at stake for critical texts in the ecosystem of contemporary dance.