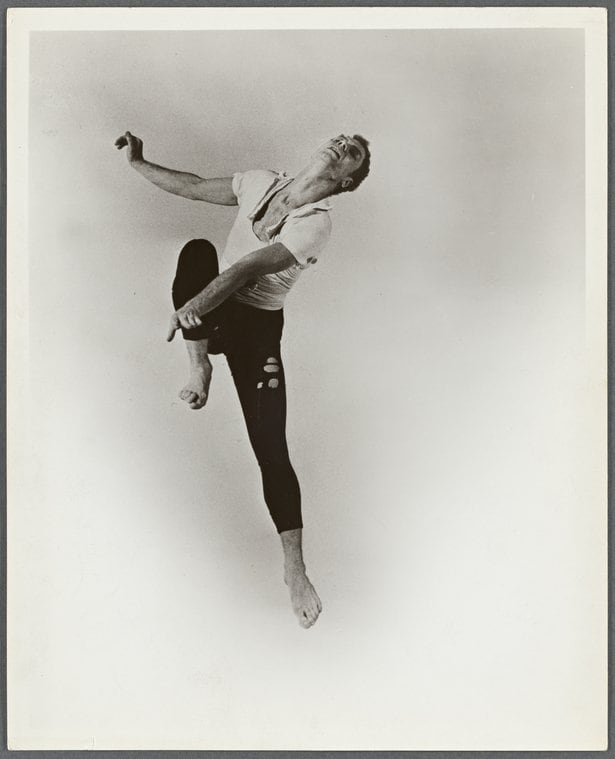

When Benjamin Millepied’s contemporary interpretation of Romeo and Juliet comes to La Seine Musicale this September, L.A. Dance Project company member David Adrian Freeland Jr. will dance the role of Romeo in two different casts, with two different partners.

This is not unusual in itself—dancers are accustomed to swapping in and out of partnerships, sometimes with little rehearsal or notice. What makes Freeland’s experience unique is that in one cast he will dance with Sierra Herrera as Juliet, and in the other he will dance with Mario Gonzalez, a reimagining of the couple as two queer men. A third cast will feature two women in the roles, and a fourth will be another heterosexual pair.

These casting choices deepen ideas already present in the story: forbidden love; a society that does not allow young people to be themselves. They’re one of several ways that Millepied’s take on Romeo and Juliet, which premiered in 2018 in Los Angeles, heightens its stakes. For one, it is a condensed version of the usually three-hour ballet, featuring the most beloved sections of the Prokofiev score. The piece “gets right to the heart of it,” says Daphne Fernberger, who plays Romeo, forgoing long party scenes to focus on the story’s emotional landmarks. According to Millepied, this symbolic, non-literal interpretation made it easier to open the work to “fluent change between sexes.”

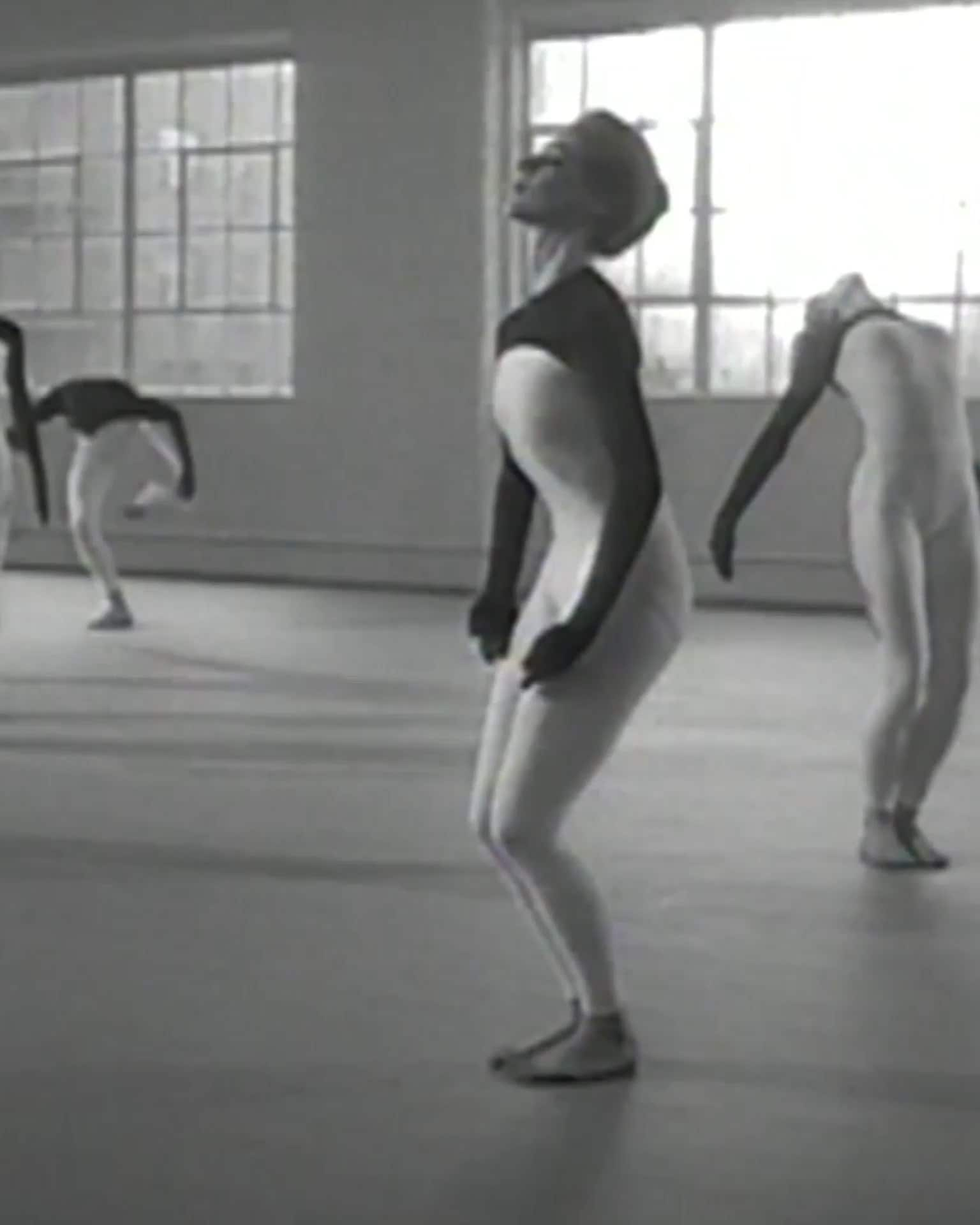

To add to the intensity, Millepied employs a cinematic trick that’s become relatively common in contemporary theater but less so in dance: Live, filmed scenes following performers into backstage rooms that double as the characters’ private spaces. “The story becomes intimate, realistic, immersive,” Millepied says. Audiences can be flies on the wall during Romeo and Juliet’s stolen moments as the live feed is broadcast into the theater—and when dancers return to the stage, “it’s like watching movie characters come out of the screen,” says Daisy Jacobson, who plays Juliet to Peter Mazurowski’s Romeo.

“It is rare for these couplings to be explicitly romantic, and even rarer for them to be part of a canonical story ballet rather than an abstract one.”

Millepied’s interpretation is far from classical. It is set in present-day Los Angeles, and, like inmost of L.A. Dance Project’s repertory, the women do not dance on pointe. Still, it is the first major production of the ballet that imagines the titular couple as queer. And though it is increasingly common to see same-sex partnerships in new ballets, it is rare for these couplings to be explicitly romantic, and even rarer for them to be part of a canonical story ballet rather than an abstract one. (Though examples exist, from Roland Petit’s 1974 Proust ou les intermittences du coeur to Matthew Bourne’s repertoire, including his queer interpretation of Swan Lake.)

Dancers of different genders sharing the same role in a ballet is a fairly new development, too. Justin Peck, for instance, has made such casting choices for several of his sneaker ballets, which have sometimes resulted in tender same-sex partnerships.

Freeland, who identifies as queer and who danced with Ailey II and Missouri Ballet Theatre before joining L.A. Dance Project in 2016, hadn’t had the opportunity to be intimate with another man onstage before this production. “To share a kiss with a guy onstage—it brings me so much joy,” he says. “I would have loved to see more of that onstage [growing up]—I still would like to see more of it now.”

While Freeland says his two Romeos don’t diverge widely, he does get to bring “more of his queer self” when dancing with Gonzalez, and says his mannerisms and gestures differ depending on who he’s dancing with. The choreography itself shifts slightly for each couple, too, though Millepied says the same is true for the casts of any of his works, and has more to do with a dancer’s individuality than their gender.

There were some partnering moments that Fernberger had to tweak as Romeo, she admits, but otherwise she learned how to use momentum and coordination rather than arm strength to lift her Juliet, Nayomi Van Brunt. Fernberger says that dancing Romeo allows her to explore qualities she doesn’t often see in roles for women: rambunctiousness, violence, anger, gutsiness, passion. She and Van Brunt have discussed what it means for both of their characters to be women, and how they can subvert the gender roles and hierarchy built into the ballet’s central relationship to “be empowered women—we’re both strong and our own selves.” Their resulting partnership is perhaps more tender than is typical, she says, and more sensitive.

As much as the pairings’ gender makeup informs how they relate to one another, and likely how audiences will perceive them, Jacobson says that gender is often not part of the equation at all in Millepied’s work. (When she was an apprentice, for instance, she understudied and went on for women and men in the company.) Jacobson brings both her feminine and masculine sides to her interpretation of Juliet, she says, and feels she would do the same if she were dancing with another woman.

There’s a tension in the way the dancers speak about the ballet between this idea of gender neutrality—that dancers can swap in and out of roles regardless of their gender—and the idea that these casting choices are intentionally and unapologetically queer. Millepied seems to want to have it both ways, though he says of his decision to cast queer couples that “it seemed impossible for me to have a narrow vision of love only represented the old-fashioned way.”

Despite its tragic ending, Freeland says some Los Angeles audience members told him after the show how moved they had been to see their own story reflected in one they’ve long known and loved. “They saw themselves onstage,” he says. “They were in tears in the moments waiting for them to kiss, because they just didn’t know if it was going to happen.”

Photo : © Lorrin Brubaker