A leading figure in minimalist music, American composer Philip Glass is the author of a prolific body of work that spans opera, ballet, chamber music, concertos and film. While his career is deeply tied to the dance landscape of the 1970s and 1980s, his heady, repetitive scores have continued to stimulate choreographers and dancers, from ballet to contemporary dance. A fertile relationship, as the artists who shared their physical experiences with Glass’s music can confirm.

If Philip Glass has an affinity with dance, it’s not by pure chance. In New York, in the 1970s, the composer lived in SoHo, an old industrial district where a host of artists resided and worked. “Simone Forti was the wife of Robert Morris, John Cage was the companion of Merce Cunningham, Bob Wilson lived with Andy de Groat and he was close to Meredith Monk, a musician and dancer,” says Renaud Machart, author of the book La Musique minimaliste. Glass was therefore in close proximity to the choreographers who were to become the pioneers of post-modern dance, he adds: “The dancers went to listen to the musicians, the musicians went to see the dancers, and it was the same with the visual artists. So collaborations between the different disciplines were quite organic.”

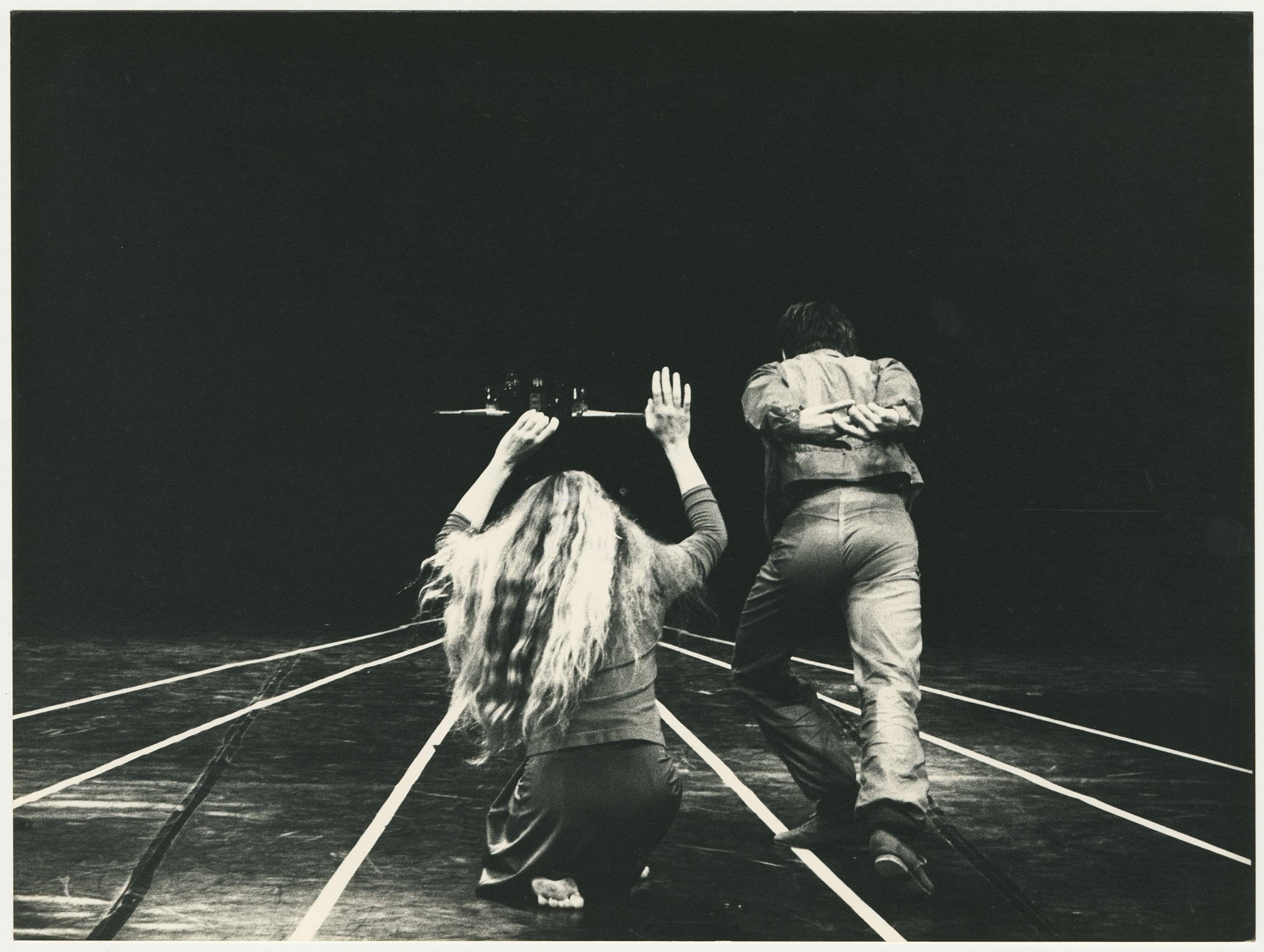

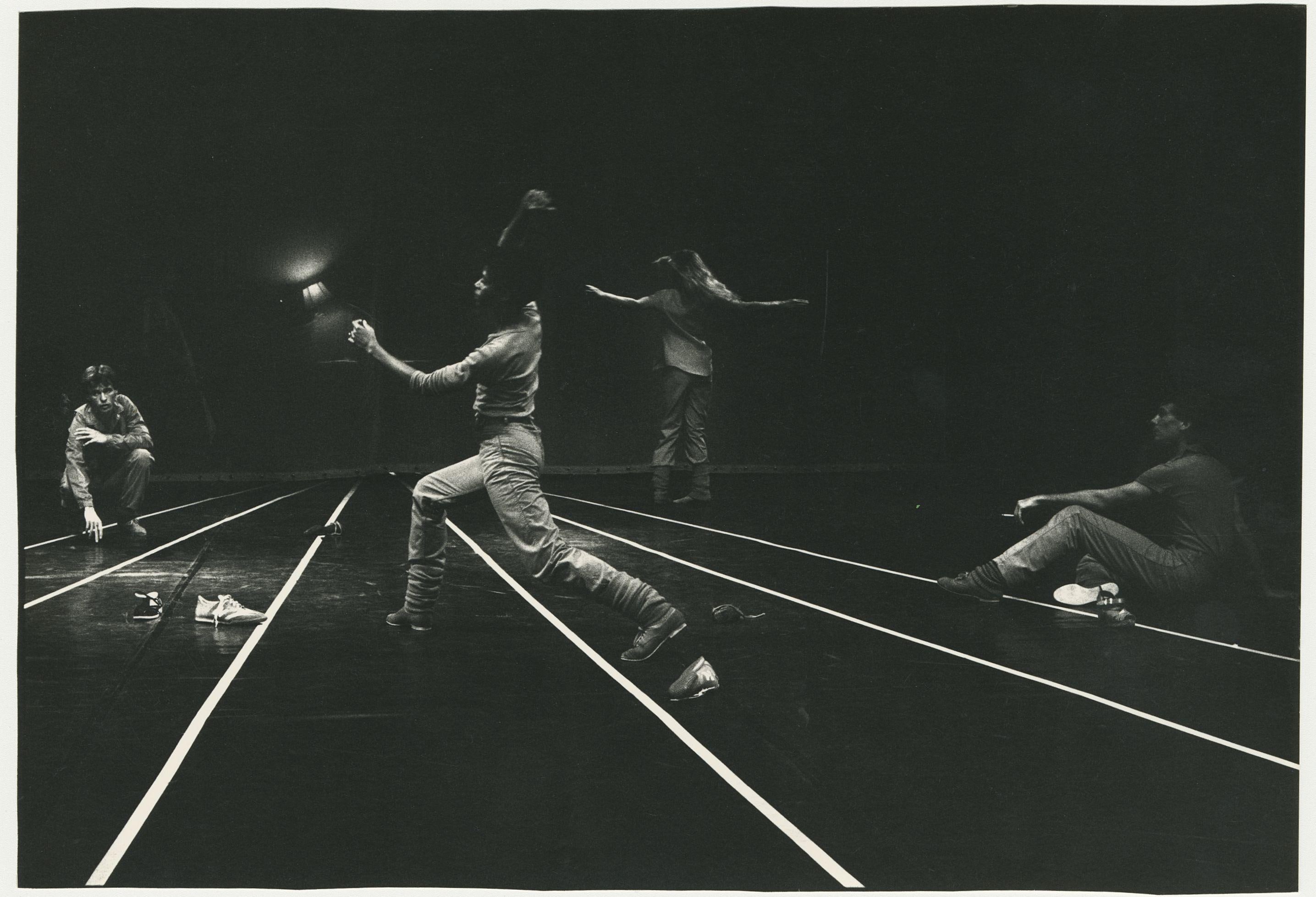

After several ambitious projects, the creation of Einstein on the Beach in 1976 propelled Glass to the forefront of the international artistic scene. Considered one of the fundamental operas of the 20th century, the project originally brought together choreographers Andy de Groat and Lucinda Childs, director Robert Wilson and Philip Glass. “It’s probably the only opera in which each component was truly conceived by artists from different disciplines, yet organically and with a unified artistic purpose,” Machart says. Andy de Groat, who was ultimately left out of the project, went on to create Red Notes (1977), based on an unedited audio recording of Einstein on the Beach. Stéphanie Bargues and Martin Barré, two members of the CCINP (a research group led by former collaborators of Andy de Groat), both danced in the 2002 revival of Red Notes and taught it to new dancers ten years later. Together, they recount: “Andy had a very singular way of listening to and organizing music. It’s the foundation of the piece: the length of the tableaux depends on it, the lights work with musical cues... It’s impossible to do without it.” Involving some twenty performers, the choreography alternates improvised passages with highly written marches: “By incorporating it, one can have a very pleasurable relationship with the music. When you’re exactly in the score, in the right place, you end up feeling as if you’re literally walking in the music.”

© « Red Notes », Andy de Groat © Médiathèque du CND – Fonds Andy de Groat

© « Red Notes », Andy de Groat © Médiathèque du CND – Fonds Andy de Groat

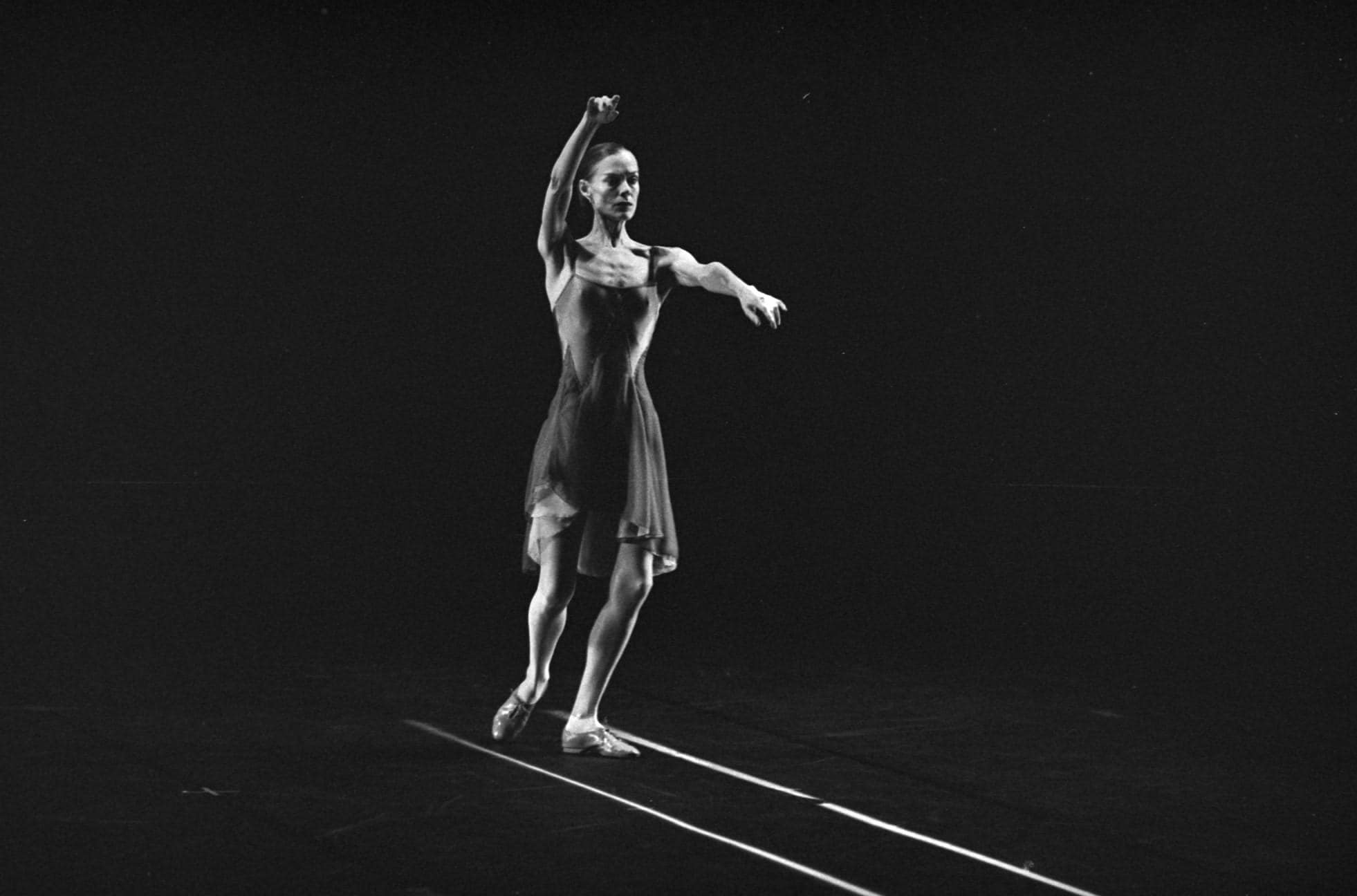

Building on the success of Einstein on the Beach, Philip Glass and Lucinda Childs reunited in 1979 to work with visual artist Sol LeWitt on a new project that would become one of the major works of post-modern dance: Dance. In the eyes of composer Michael Riesman, the musical director of the Philip Glass Ensemble, Dance remains to this day one of Glass’s most accomplished collaborations: “Lucinda understood Glass’s music perfectly, its structure, its evolution. She made the score visible: dance and music are one.” A loyal dancer and then assistant to Lucinda Childs, Ty Boomershine has observed over the years this symbiotic relationship between artistic disciplines, yet he says there was a discretion to the bond between Childs and Glass themselves: “Philip never came to see a studio rehearsal, I never heard him comment on the dance... Except that one day when he told me he was fascinated by the way Lucinda visualized and appropriated his music to propose another form for it.” Ty Boomershine has vivid memories of his years interpreting Dance. “I can say without hesitation that her dance never subjugates the music, nor does it dominate it: the two mediums coexist, responding to each other. But it took me several years to grasp this and to understand the complexity of this relationship.”

Dance was brought into the repertoire of the Lyon Opera Ballet in 2016, and it continues to be performed on international stages. Noëllie Conjeaud, who performed the solo originally danced by Lucinda Childs herself, found a similar sense of concord between sound and gesture: “The first time I heard the music, I immediately associated it with movement. The music dictates the steps, and vice versa. You can’t have one without the other; it’s as much mathematical as it is organic.” Having danced this solo over a hundred times, Noëllie Conjeaud now discerns every nuance of the music. “It’s considered repetitive, but I never tire of it. I’ve listened to it so much that I can identify all the instruments, the cuts and variations. When I dance the solo, I really feel like I’m one with the music,” she says.

“When I was younger, I often practiced and experimented in the studio with Glass’s music,” says the Belgian choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. “It instils a flow, an energy, it doesn’t impose any discourse, it offers a lot of space for interpretation.” When Cherkaoui was invited in 2017 by Theater Basel to stage Glass’s opera Satyagraha (1979), he immediately fell in love with the heady score, sung in Sanskrit: “Sometimes it takes me a while to fall in love with a piece of music. Here, I was immediately drawn in by the motifs, the complexity and all the layers it contains.” Accompanied by a large team of singers and dancers, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui staged and choreographed this Indian saga, which lasts over three hours and is inspired by the life of Gandhi, as a long flow of uninterrupted movement: “I saw this music as a form of marathon, and I tried to find a way of reproducing this effort in the choreography.”

© « Red Notes », Andy de Groat © Médiathèque du CND – Fonds Andy de Groat

© « Red Notes », Andy de Groat © Médiathèque du CND – Fonds Andy de Groat

A former dancer with Twyla Tharp’s company, choreographer Petter Jacobsson took part in the 1993 revival of In the Upper Room (1986), set to Glass’s eponymous music, and he was also confronted with its demanding score and exhilarating melodies. “The choreographic style is extremely precise and intense,” he says. “The relentless rhythm of the music contributes to this drive: you’re caught up in a torrent of energy from which you can’t tear yourself away until the last note.” As the director of the CCN – Ballet de Lorraine since 2011, he brought this piece into the repertoire, with its distinctive combination of classical and contemporary vocabulary, pointe shoes and sneakers. Valérie Ly-Cuong, a dancer who has been with the company for almost twenty years, remembers it with enthusiasm: “The choreography is extremely physical, and fortunately the music is there to carry and support us. It was a great pleasure for me to dance to this music, to experience it physically. It’s very effective, intoxicating and it inevitably works, both for the audience and for the performers. It’s hard not to be affected by it while listening to it.”

Still heard on numerous stages today, the back catalogue of the American composer, now 86 years old, has survived through decades and lost none of its appeal. According to Machart, the author, Glass is even the composer who has best expanded the vocabulary of minimalist music and made it evolve, bringing it to the attention of the general public, notably through his operas and even more so through his scores for films. "There’s something about him that’s seductive, that stays in the ear, that’s immediately recognizable,” Machart says. “It’s music that musicians want to play, and that audiences still want to hear” – and to which dancers still want to dance.

Wilson Le Personnic holds a BA in Fine Arts from Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, and a degree from École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Paris-Cergy, as well as an MA in Dance from Université Paris 8. He now regularly works with dance artists and writes for theatres and press.

Photo de couverture : « Red Notes », Andy de Groat © Médiathèque du CND – Andy de Groat Funds