TAO Dance Theater is one of the few Chinese companies to make regular appearances on Western stages, drawing equally on locally informed aesthetics and the formalism of postmodern dance and its successors. Scholar Hentyle Yapp profiles the troupe, whose singular style rethinks how we discuss non-Western dance beyond solely the universal or the particular.

© Fan Xi

© Fan Xi

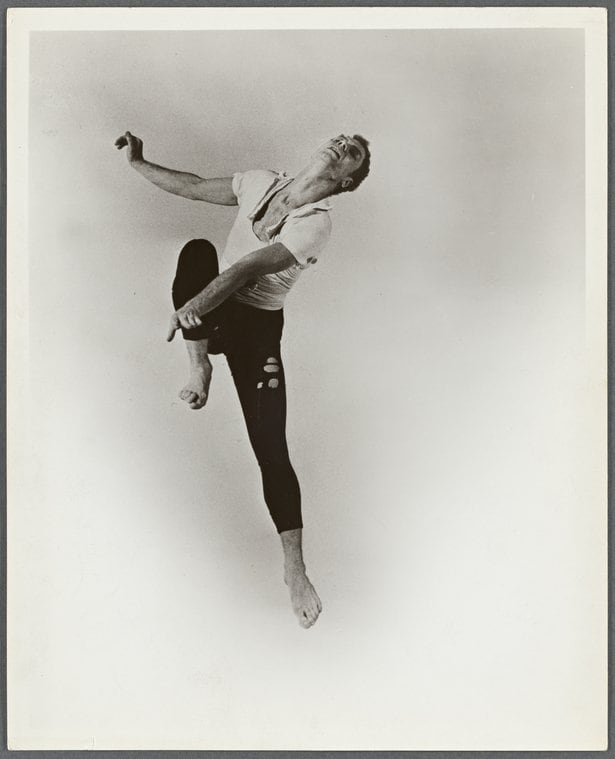

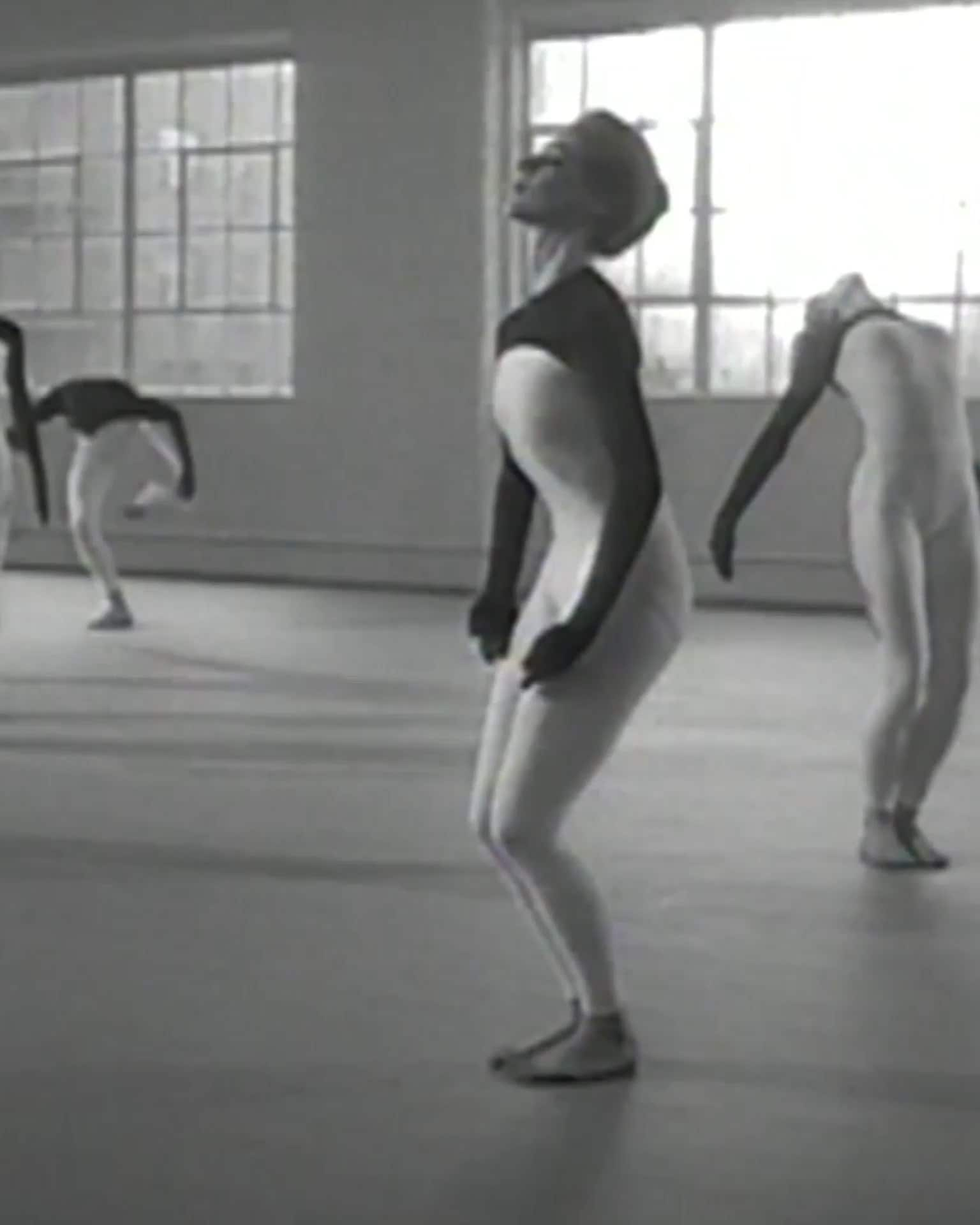

TAO Dance Theater began in 2008 as a collaboration between Tao Ye, Duan Ni, and Wang Hao, quickly emerging on the global contemporary and modern dance scene. Since then, the company performed across stages in Australia, Asia, the Americas, and Europe. One of their early choreographic masterpieces, 4, established their renown in 2012, helping TAO Dance Theatre become one of the most widely circulated contemporary dance companies from China. Lasting thirty minutes, 4 is emblematic of the company’s larger aesthetic: formalist experimentation that is at times fast-paced, with explosive movements exploring kinetic ricochets across and through the dancers’ bodies with minimal muscular engagement. The company has continued creating works in a numbered series, progressing from 2 all the way up to, most recently, 16 and 17.

Since Tao Ye, one of the choreographers, was educated in Chongqing and worked with Jin Xing Dance Theater and Beijing Modern Dance Company, most journalists and popular discourse have situated the artist and the company primarily within the context of China. However, his use of movement, sound, and costume draws on a long legacy of aesthetic experimentation and formalism, prompting many reviewers to compare him to US and European luminaries like Lucinda Childs and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. This formalist approach can be seen either as an all-encompassing lens by which to understand Tao’s choreography or as an aesthetic at odds with his Chineseness. Yet Tao Dance Theater is neither merely an example of a Chinese company nor simply a universal instance of modern and contemporary dance; instead, their unique aesthetics and genealogies expand how we consider and discuss dance increasingly emerging from the non-West.

Tao Ye was first introduced to modern and contemporary dance while performing in an army troupe. During an impromptu class, a teacher from Shanghai’s Jin Xing Dance Theater introduced the choreographer to the aesthetics of modern and contemporary dance. Afterwards, Tao Ye went on to work for two of China’s largest modern dance companies, as mentioned above. Within China’s broader dance ecosystem, TAO Dance Theater certainly draws from a rich genealogy of modern/contemporary dance artists from China, Taiwan, Japan, and Hong Kong. Choreographers such as Lin Hwai-Min, Shen Wei, Yin Mei, and Eiko & Koma, among others, have established and expanded our understanding of modern and contemporary dance emerging across Asia and its diasporas.

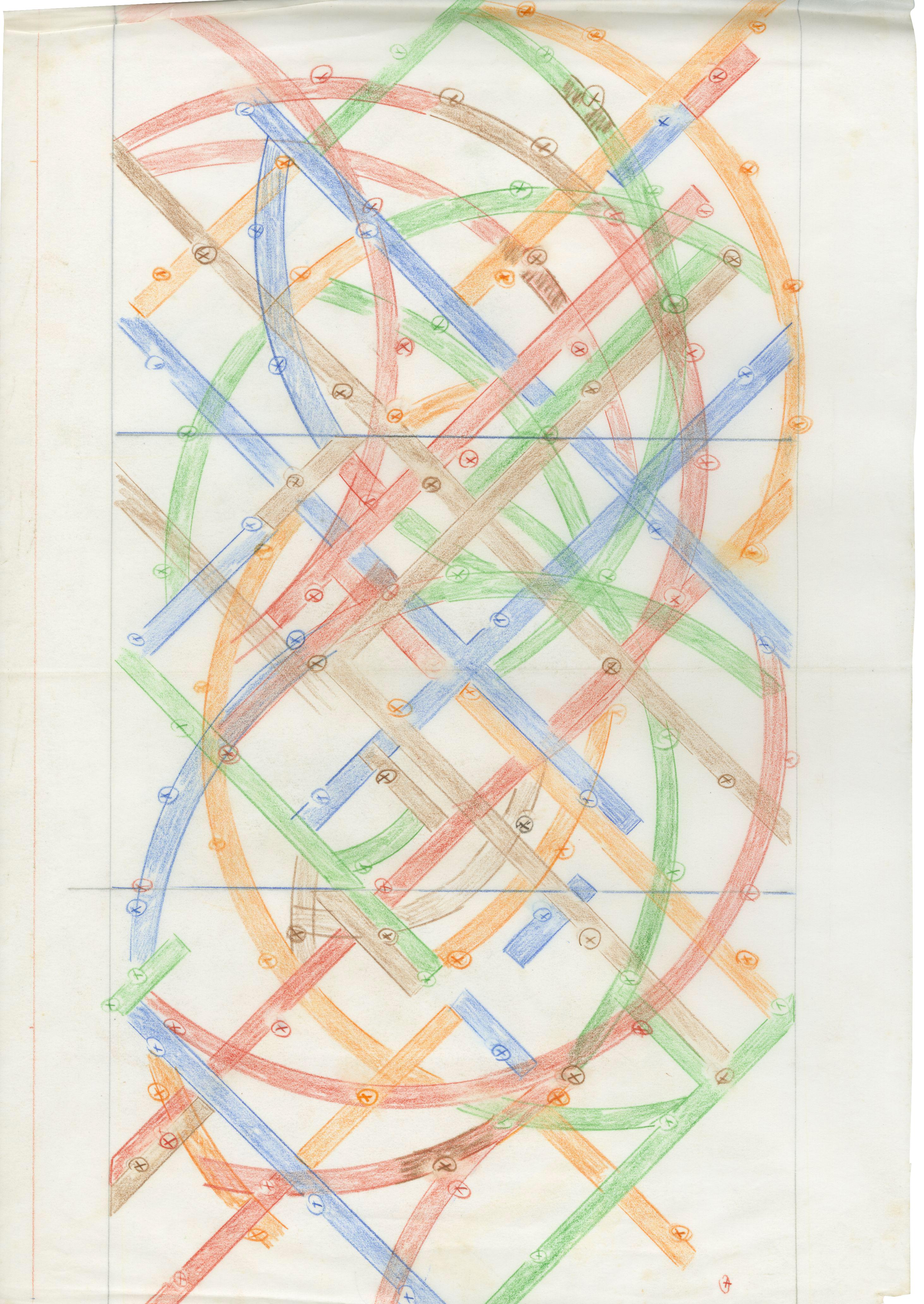

In addition to the choreographers mentioned above, TAO Dance Theater works within a dance vocabulary that emphasizes movement experimentation, drawing from influences such as Trisha Brown’s release technique, while moving toward aesthetic form. Since training in modern dance in China, Tao Ye has constructed what he calls a “circular movement system.” To generate movement, the choreographer asks dancers to activate all limbs and joints in ways that explore the relationship between different points: a point that triggers motion, another that initiates movement from one point to another, and the movement of a single point. Together, this system trains dancers to develop a dual sense of control and release. Through such experimentation, the company uses the body to explore ideas centered on formalism, in the vein of Merce Cunningham, Lucinda Childs, Ralph Lemon, and Boris Charmatz. What TAO Dance Theater has in common with these choreographers is a commitment to experimenting with movement and its possibilities in order to expand and reconsider our understanding of movement, the body, dance, time, and space.

The company operates across, within, and beyond these two genealogies that draw from across Asia and the larger world. The company is neither simply a particularized example of a Chinese company nor purely part of a universal dance community centered on formalism and experimentation. Its existence as both complicates the easy, automatic narratives often discussed separately. By placing these perspectives together, we might begin to ask a different set of questions: How have artists drawn from their particular contexts to engage broader, universal aesthetics and questions—not only Tao Ye in contemporary China, but also Merce Cunningham in the US in the 1960s? Why is our available discourse structured in ways that do not allow for a more expansive engagement with both the universal and the particular?

By delving into the multiple traditions and genealogies that TAO Dance Theater works within, we begin to open up the discourse around movement, especially as more companies from beyond the major centers of contemporary and modern dance (presumed to be the US and Western Europe) continue to circulate. These companies are not merely emblematic of their local contexts, reducing dance to an ethnographic snapshot of a locale like China. Nor are they solely part of some universal language centered on movement and the body. Rather, these companies provide the opportunity to rethink and rework how we discuss dance beyond the dichotomy of the universal and the particular.

Hentyle Yapp is an associate professor of performance studies at the University of California, San Diego. He is the author of Minor China: Method, Materialisms, and the Aesthetic and the co-editor of Saturation: Race, Art, and the Circulation of Value. A former professional dancer, he has performed with companies in New York, Taiwan, and San Francisco.