Brazilian dancers Luciana Sagioro and Lucas Resende have crossed the Atlantic to study dance in France – the former at the Paris Opera Ballet School, the latter at the training center of the Angers CNDC. Their respective paths suggest French ballet and contemporary dance remain influential abroad, in no small part due to their historical prestige.

When she left Rio de Janeiro to move to Paris at the end of August, 16-year-old Luciana Sagioro was ready to live “a dream.” A few months earlier, after winning the “Young Hope” scholarship for her third place at the 2022 Prix de Lausanne, a prestigious international ballet competition, she was offered spots in eight European dance schools. She picked the Paris Opera Ballet School. “It was an incredible opportunity,” she says. “It’s notoriously selective, very few people are invited to train there. It was a no-brainer for me.”

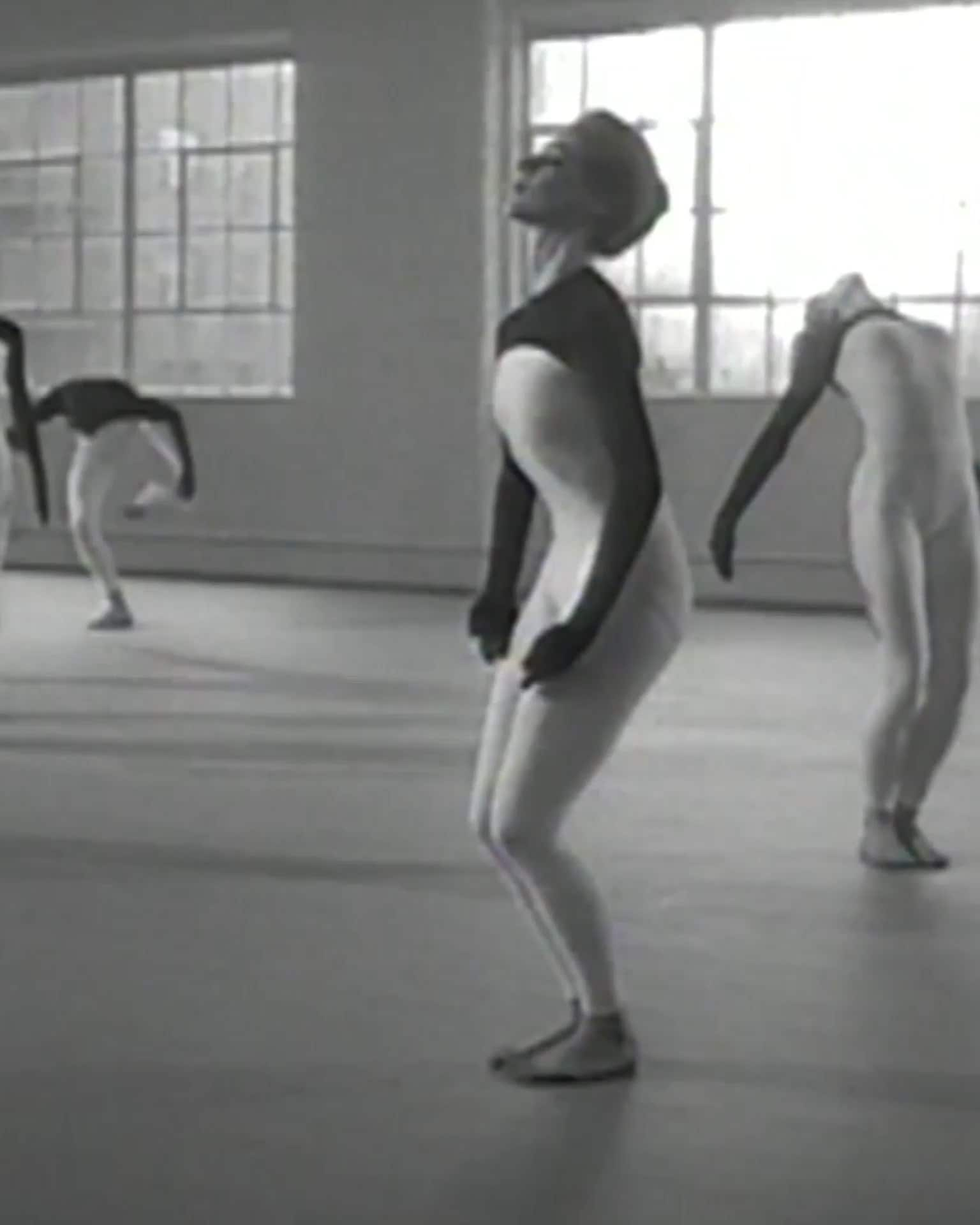

Studying contemporary dance in France was a less obvious choice for Lucas Resende. After starting his career as a dancer and choreographer in Brazil, he was deeply moved by En Atendant, a 2010 work by Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. “That piece changed my life,” he remembers. “That’s when I knew I had to go to Europe.” He made it to Brussels in 2013, and first applied to study at P.A.R.T.S., the school De Keersmaeker founded: “I knew it would be hard, because most schools didn’t accept students my age.” In the end, he joined the Angers CNDC training center in 2021, after meeting its director, the choreographer Noé Soulier – and auditioning over Zoom due to the pandemic.

Brazilian artists have long been a part of the French dance scene, but Sagioro and Resende say that the opposite isn’t necessarily true. While Resende had the opportunity to see contemporary pieces by Emmanuelle Huynh and Mathilde Monnier during Belo Horizonte dance festivals, Sagioro says that “it’s very rare to see French ballet dancers in Brazil.”

Despite the distance, the French choreographic landscape was a major source of inspiration for them during their training in Brazil, thanks to recordings of shows and online video clips. When he was with the Primeiro Ato Company and studying for his BA in dance at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), Resende studied the works of “Laurence Louppe and great philosophers like Foucault or Bataille” – an “enriching” brush with French theory, which he encountered again at the CNDC. “I want to do research,” he says. “I want to learn how to talk about what I’m doing.” Resende finds that in France, there is more emphasis on intellectual training than in Brazil, where practice is at the core of dance training, and says his way of moving has already been impacted by the change of scenery. “I feel that my way of dancing is less savage here, less frenzied, because it’s such a calm environment. In Brazil everything is so fast, whereas Angers is such a small and safe little town.”

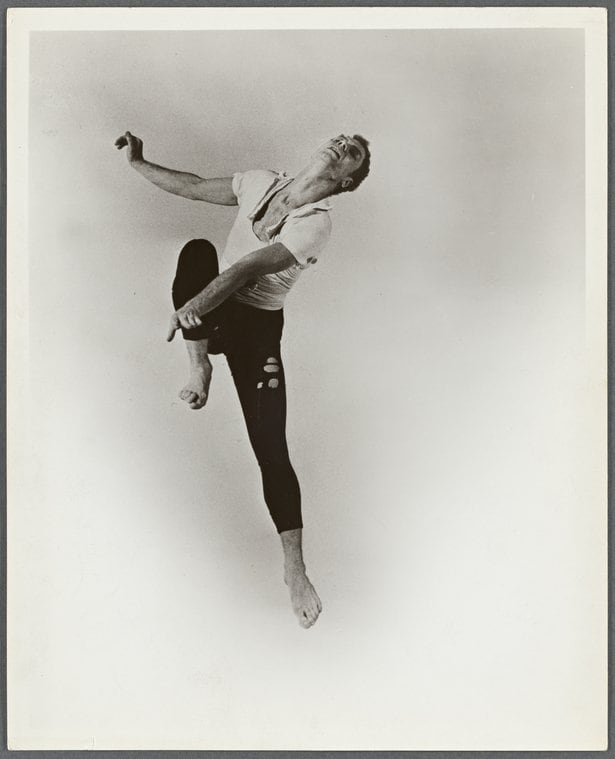

© Luciana Sagioro, Prix de Lausanne © Gregory Batardon

© Luciana Sagioro, Prix de Lausanne © Gregory Batardon

In the ballet world, the prestige of French dance makes its training programs all the more attractive – for other historical reasons. While Sagioro was initially trained in the curriculum of the Royal Academy of Dance and then in the “refinement of the body and expressiveness” of the Vaganova style, she chose France to “honor the origins of ballet” and suggests that the Paris Opera Ballet remains the guardian of “the great traditions of dance” – an image the French company has maintained abroad.

“Technically speaking, we work mainly on legwork and footwork, and emphasize the purity of movement,” says the young dancer a few months after starting at the Paris Opera Ballet School.

South American dancers remain few and far between in French companies. As the only Brazilians in their schools, Sagioro and Resende were first confronted with the language barrier. Even though Resende knew that “several Brazilian artists, like Volmir Cordeiro and Elisabeth Finger, had trained at the CNDC,” the culture shock “made it very difficult to be the only Latino dancer there.” As for Sagioro, she believes the relative absence of Brazilian dancers is one of the reasons why her presence at the Paris Opera is important: “I’m representing my country here, and who knows, maybe it will create more opportunities for talented young Brazilians in the future.”

Said future, to both of them, will involve intercultural dialogue. As a dancer and choreographer, Resende wants to live “between Brazil and France, and work with other artists.” He “misses a lot” his country, but acknowledges that “it’s easier to have access to cultural and creative opportunities” in France than in Brazil, where the lack of stability in public cultural policies is a major obstacle. Sagioro, who hopes to join the Paris Opera’s corps de ballet, wants to find a balance between “the norm” imposed by the French company and her own origins – and perhaps “show France a glimpse of the Brazilian style.”