From Germaine Acogny (Senegal) to Salia Sanou (Burkina Faso), Rachelle Agbossou (Benin) and Florent Mahoukou (Congo), African-born artists seem to concur: the continent’s contemporary dance scene relies heavily on Europe for institutional funding, especially France. At home, the performing arts rarely benefit from national and local cultural policies. As a result, African dance professionals have to contend with a system that long encouraged artists to model their work on the expectations of the western market – and are now attempting to shift the focus back to the continent, rethinking the Global South-North relationship in the process.

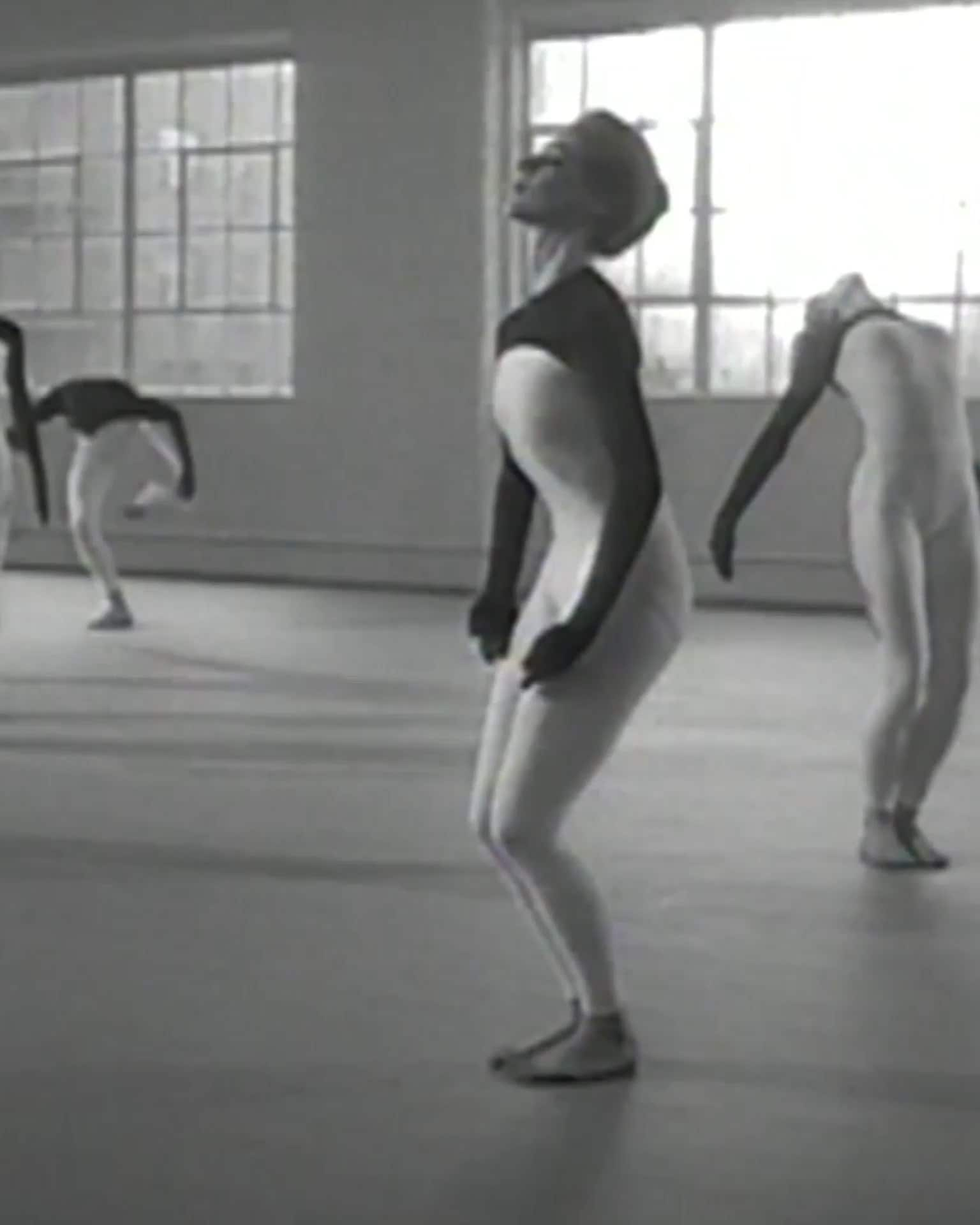

Paris, October 2023, quai Conti on the Seine river’s left bank. Under the palatial dome of the historic Institut de France, Germaine Acogny received the prestigious Grand Prix for choreography from the Academy of Fine Arts. According to custom, the Franco-Senegalese choreographer will divide the prize’s 30,000€ award between three artists whose work she admires: Rachelle Agbossou, Amadou Lamine Sow, both from Benin, and Ange Kodro Aoussou-Dettmann, from Côte d’Ivoire. Less than two months later, ‘Mama Germaine’ as many African artists like to call her, was celebrated in Paris again – but this time it was for her new group performance, Dialow Project. The piece, directed by Mikaël Serre, denounces the planned construction of an industrial harbor in Toubab Dialaw, a coastal fishing town south of Dakar where she created the École des Sables with her husband Helmut Vogt. Acony’s school, which has become a renowned institution for dance instruction over the last twenty years, is now threatened by this massive construction project.

© Dialow Project de Mikaël Serre et Germaine Acogny © Joseph Banderet

© Dialow Project de Mikaël Serre et Germaine Acogny © Joseph Banderet

Honors on one side, precarity on the other – with the added particularity that both events occurred in the French capital, illustrating how strategic France (and, more broadly, Europe) is in the creation, financing, touring, and promotion of contemporary African dance. Dance Reflections, a philanthropic initiative of the French jewelry company Van Cleef & Arpels, provides funding for the scholarships that École des Sables bestows each year on thirty dancers from across the African continent to take part in the school’s Afrique Diaspora program. Initiated in 2022 and divided into three intensive ten-week modules, the theme of this year’s edition, which will end in July, is ‘Where are the works of black artists?’. “Supporting education, along with transmission and creation, is one of our three core values,” explains Serge Laurent, director of Van Cleef & Arpels’ Dance and Culture program. “As Western curators, we must be aware of other cultures and ask ourselves what Africa needs. We also have to be vigilant about keeping that development local, on the African continent.”

Things aren’t much different when it comes to producing and promoting dance pieces. “Most opportunities to produce works and finance travel expenses come through French Institutions or the EU,” says choreographer Rachelle Agbossou. “In Benin, there is no official state funding or structures to help pay artists in the rare venues that host dance performances.” Thanks to the money Agbossou will receive from Acogny’s Academy of Fine Arts award – a “breath of fresh air!” – she’ll be able to move her Walô Dance Center, created in 2020 in Abomey-Calavi, to a location she’ll own, which should prevent her from being subjected to future rent hikes. When Agbossou created her Center, she received financial support from the Benin Arts and Culture Fund, as well as from the European Union. Government support for dance in Benin remains sporadic, however, and private funders “don’t think it’s worth investing in yet”. As a result, says Agboussu, “it’s a constant struggle.”

© Agodjie, Rachelle Agbossou © Sophie Négrier

© Agodjie, Rachelle Agbossou © Sophie Négrier

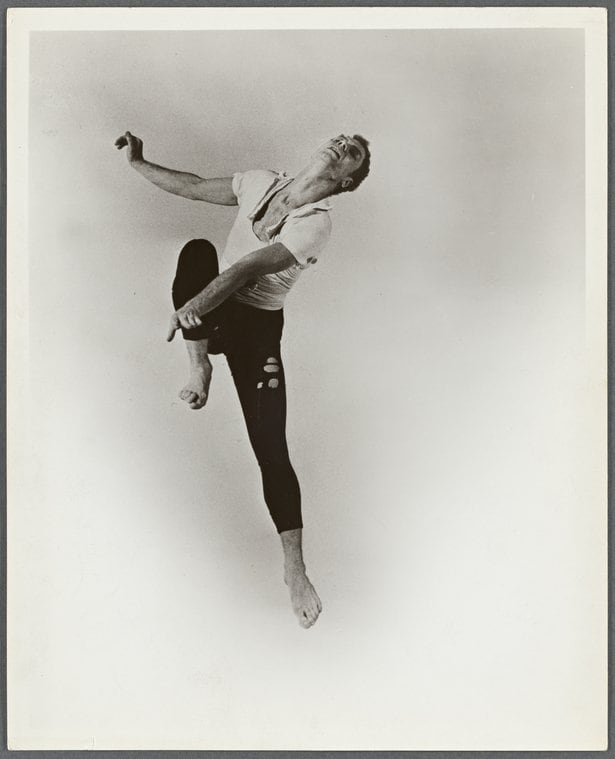

Florent Mahoukou won’t contradict her. The Congolese choreographer relocated to Pointe-Noire in 2017 after a decade of living and working in France. At the time of his move he had resigned himself to quitting dance as a career, aware that making a living as an artist in his home country was almost impossible. Mahoukou recounts his doubts and reflection in a documentary titled Face to Face. Shot in Pointe-Noire with rudimentary means, the film has received prizes and accolades in several festivals since its 2021 release. Meanwhile, its creator was embarking on a radical career change, training to become a “senior non-destructive testing technician” in the industry. This new job now allows Mahoukou to self-finance his artistic practice, which he still “enjoys very much.” He plans on offering his work to foreign curators online, “on the condition that the internet signal is good enough.”

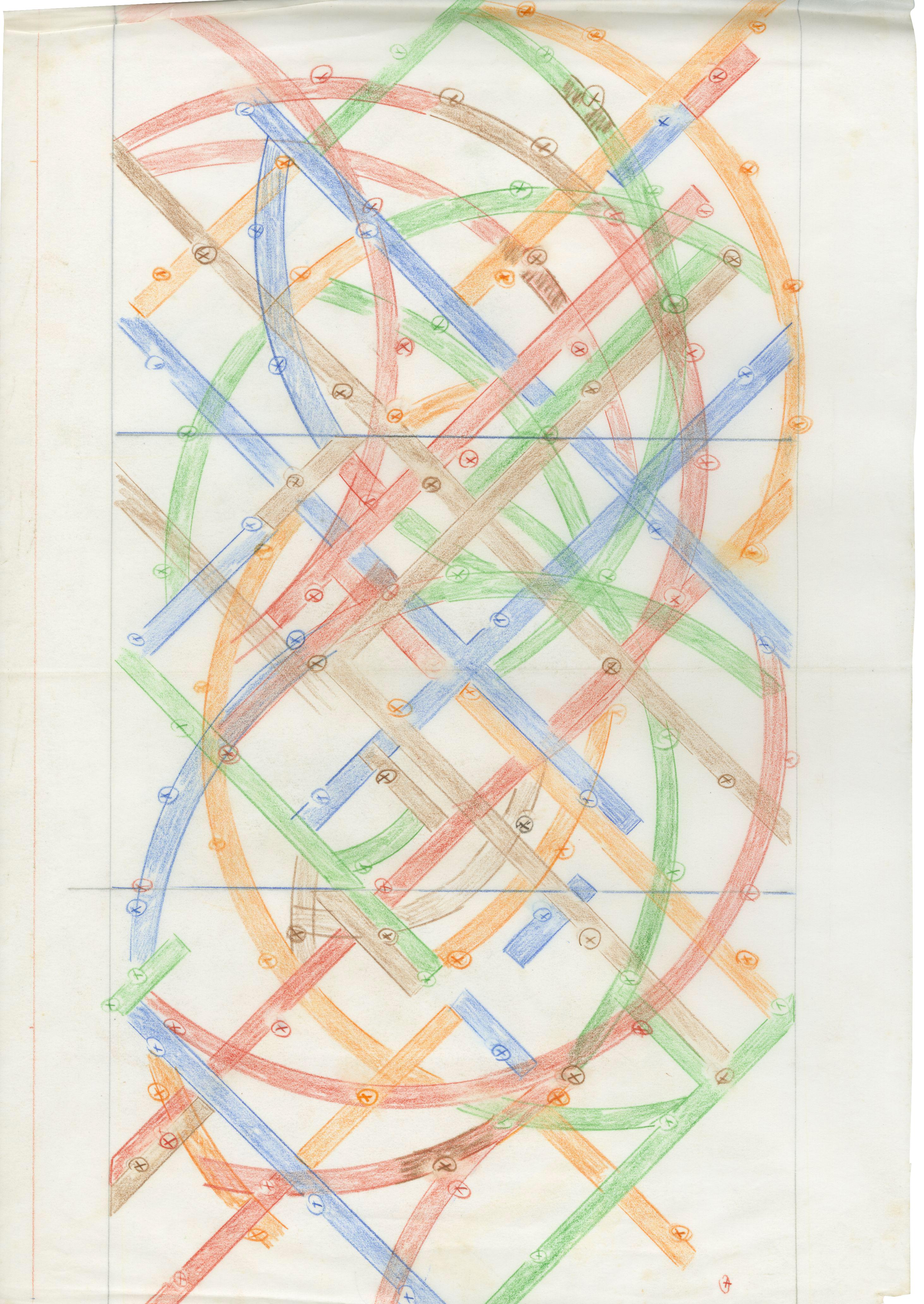

Salia Sanou, co-director of the La Termitière Center for Choreographic Development in Ouagadougou and founder of the Dialogue de Corps festival, chose to adapt to changing circumstances. His take is that “if there is support here and there in Africa, it’s never adequate for what we actually need. In Burkina Faso, as in many African countries, the priority is not dance, but education, building and maintaining roads, healthcare… It’s no use sticking to a moral position where African dance should be financed by African money. It’s better to expand the perspective worldwide and to go look for funding where it’s actually available.” La Termitière is a good example. When it was built in 2005, the French government provided funding for the construction and the lot was given to the association that manages the CDC by the Burkinabe state, which pays the water and electricity bills amounting to 50% of the Center’s yearly budget. However, in the absence of long-term structural funding within the country, La Termitière’s activities, including residencies and training programs, are financially dependent on calls issued by the Institut Français and other foreign sources of project-based funding. The trade-off is that accepting the policies and priorities of European institutions risks conditioning African artists to cater their creations to Western tastes.

© Capture d'écran du film Face to Face de Florent Mahoukou

© Capture d'écran du film Face to Face de Florent Mahoukou

“The French are historically the main providers of support for projects on the African continent,” says Sophie Renaud, director of Cooperation and Social Dialogue at the Institut Français. “We know their ecosystems and we provide long-term support, whereas others are only interested in specific people or fields, with financial capacities that sometimes exceed ours but are never geared towards the long-term.” Her fervent wish is that “other structures, either local or international, pitch in to help our institutes and support these artists’ projects.” This is why the Institut Français has handed over the management and direction of the “Biennial,” the main dance event on the African continent, to a committee composed of prominent figures in the African dance world – while remaining its top funder.

The 2024 edition, which was held in Maputo, Mozambique, was jointly directed by Hafiz Dhaou (Tunisia), Taoufik Izzediou (Morocco), Qudus Onikeku (Nigeria), Salia Sanou (Burkina Faso), Virginie Dupray (RDC-France), and host Quito Tembe (Mozambique), director of Bienal Kinani. Beyond the diversity and quality of the shows featured in the event, Tembe congratulates himself on “taking a risk and programming full-length pieces with many dancers,” like South African choreographer Mamela Nyamza’s Hatched Ensemble or Mozambican choreographer Idio Chichava’s Vagabundus., well beyond the usual criteria for tour in the West. These types of shows, which are generally too cumbersome to tour in the West, are a way, says Tembe, for African artists to “assert our own language and our own dance, without looking to produce pieces for the European market.” The success these pieces found with the almost 300 curators present in the event – including about 30 from African countries – boosts his conviction that it is indeed possible for things to evolve favorably. Even if it means programming performances in non-conventional venues, like city halls or post offices, to make up for the scarcity of dedicated venues – all in order to have “dance everywhere” for eight days straight.

Isabelle Calabre is a journalist specializing in culture and dance, who works with several print and online magazines. She has written for a number of theaters and festivals and is the author of several books on hip-hop as well as the YA book Je danse à l’Opéra (éd. Parigramme). Additionally, since 2018, she has conducted research on West Indian and Guyanese quadrilles (Creole social dances). In 2020, she was awarded funding from the Centre national de la danse for that project.

Afrique Diaspora Program module 3

From April 29 to July 7 in École des Sables, Toubab Dialaw, Senegal

Hatched Ensemble

Choreography: Mamela Nyamza

June 18 in Lille during the Latitudes Contemporaines festival

Vagabundus

Choreography: Idio Chichava

In June at the Atelier de Paris CDCN during the June Events festival

Face to Face

Conception: Florent Mahoukou

Walô Dance Center

Abomey-Calavi, Benin

CDC La Termitière

Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

Bienal Kinani

Maputo, Mozambique

École des sables

Toubab Dialaw, Senegal