Has any other dance company been featured on screen as often as Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal? It’s a reasonable question when perusing the long list of films in which Bausch and her dancers appear. From television documentaries to fictional worlds on the big screen, from Pedro Almodovar to Chantal Akerman, not to mention Bausch’s own turn behind the camera, Tanztheater Wuppertal’s 40-year filmography is extensive, with Florian Heinzen-Ziob’s Dancing Pina the latest addition. How has Bausch’s choreography forged a bridge between the worlds of dance and moving images? And how has it evolved over time?

With its prominent mix of sound, sets, and costumes, the interdisciplinary nature of Tanztheater Wuppertal’s production design lends itself well to the audiovisual world. The company is also a cosmopolitan one, touring regularly since its inception, which has multiplied the potential for cinematic collaborations abroad. But it is Bausch’s powerful presence and her company’s explorations of the human condition that have sustained the film world’s long-term interest. Chantal Akerman refers to a “very strong emotion that I’m unable to define” in Un jour Pina a demandé (One Day Pina Asked, 1983).

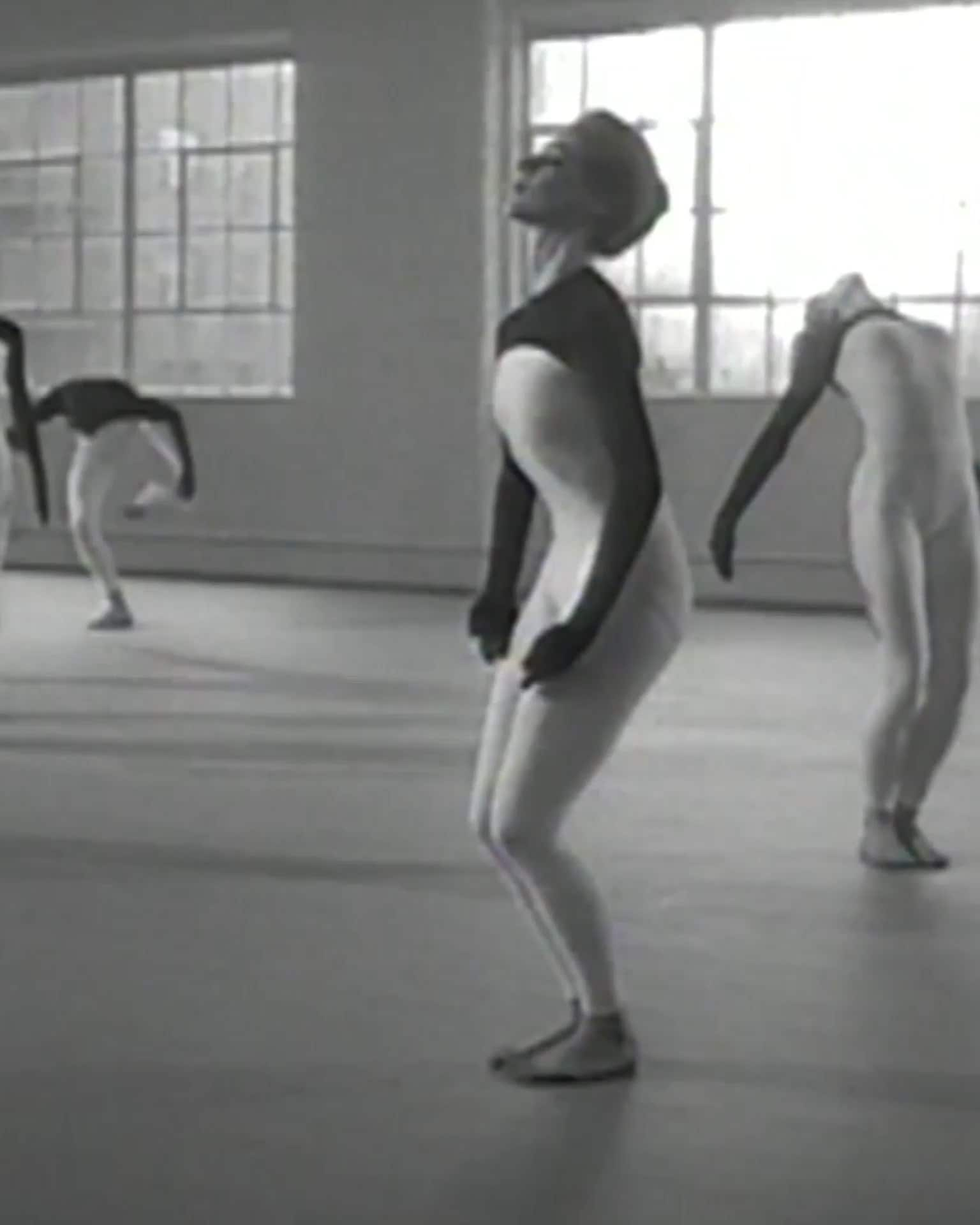

The influential Belgian filmmaker’s portrait of Tanztheater Wuppertal was released a mere decade after the company’s founding. Although initially made for television, the 57-minute documentary remains a staple at arts institutions due to Akerman’s subtle camera work composed of long, fixed takes. Merging extracts from performances, as well as behind the scenes footage, Un jour Pina a demandé offers a powerful immersion in Bausch’s early creative universe.

© « Dancing Pina », Florian Heinzen-Ziob © Dulac Distribution

© « Dancing Pina », Florian Heinzen-Ziob © Dulac Distribution

Although Bausch rarely performed her own choreography, her haunting role in Café Müller (1978) left an indelible mark on two other pillars of auteur cinema, Federico Fellini and Pedro Almodovar. Bausch’s performance with closed eyes and outstretched arms inspired the Italian director to cast her as a blind aristocrat in one of his final films, E la nave va (And the Ship Sails On, 1983). Joining an ensemble cast of eccentric characters, Bausch’s Princess is thrown into a jumble of surreal and comedic vignettes, not unlike those found in her own stage creations.

Discerning audiences may notice a poster of Bausch from Café Müller in Pedro Almodovar’s 1999 feature Todo sobre mi madre (All About My Mother). His next film, Hable con ella (Talk to Her, 2002) opens with a passage from the same performance danced by the Wuppertal company. The scene initiates an improbable encounter between two men and underscores the film’s contrast between mobile and immobile bodies. Almodovar noted that Bausch’s dancing in Café Müller “best represented the limbo in which my story’s protagonists lived.” The choreographer’s emotionally-charged movements are so central to the tangled melodrama that the film ends with another Tanztheater Wuppertal performance, the more optimistic Masurca Fogo.

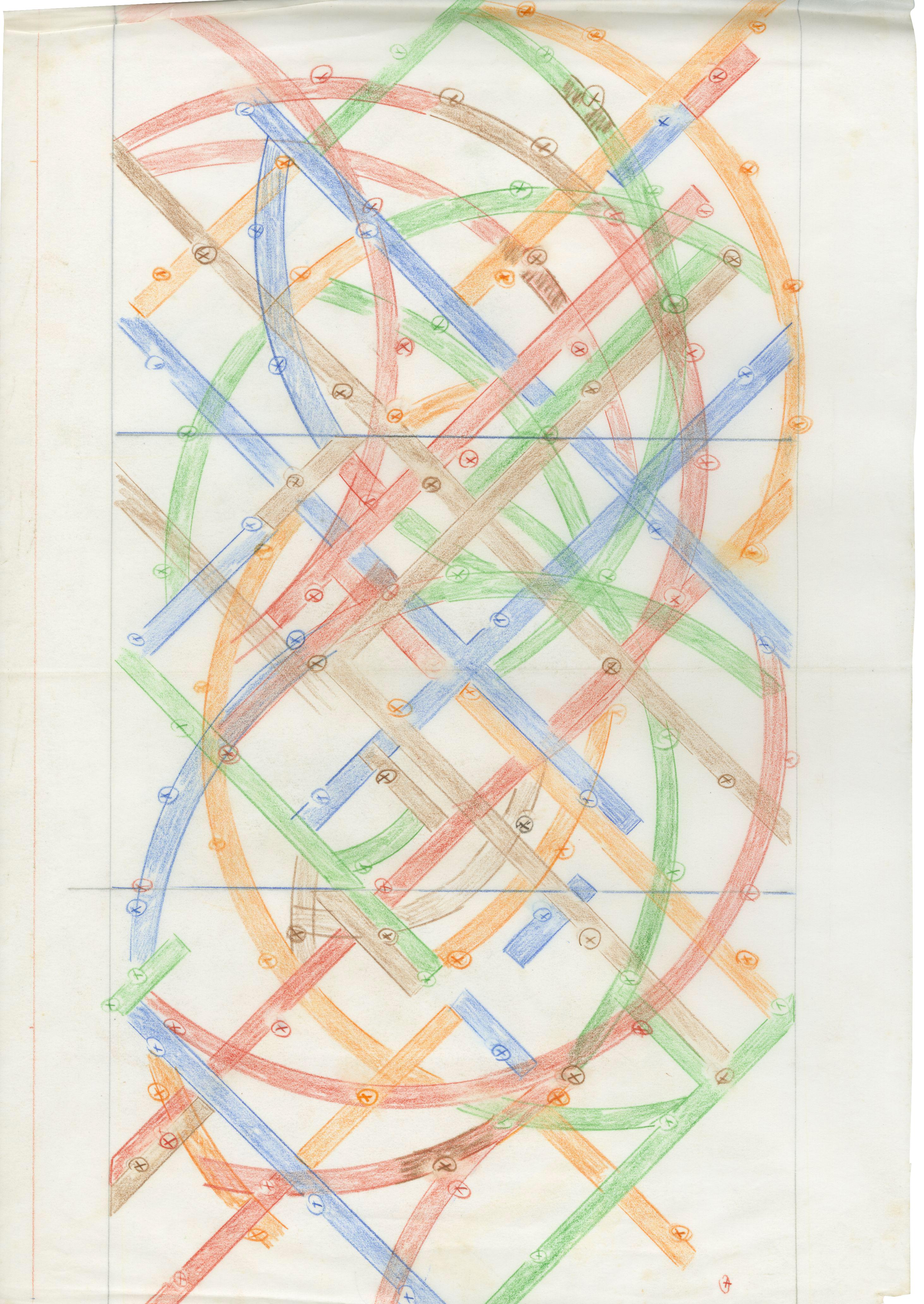

Between collaborations, Bausch herself created a unique work of choreography for the screen in Die Klage der Kaiserin (The Plaint of the Empress). Filmed between 1987 and 1989, Bausch’s screendance opens with a woman struggling to orient an unruly leaf blower across a steep incline covered in autumnal foliage. Exploring the possibilities of site-specific movement, Bausch also drew on the intimacy of the camera in close-up and medium shots to focus on the nuanced expressions of her performers.

© « Dancing Pina », Florian Heinzen-Ziob © Dulac Distribution

© « Dancing Pina », Florian Heinzen-Ziob © Dulac Distribution

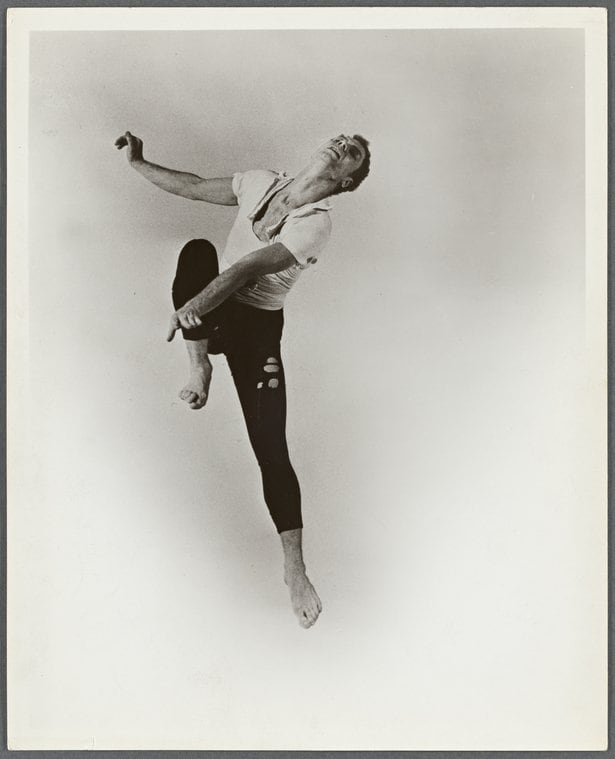

Meanwhile, the small screen continued to host multiple documentaries on Tanztheater Wuppertal, including Eva-Elisabeth Fischer and Frieder Käsmann’s Das hat nicht aufgehört, mein Tanzen (It Did Not Stop, My Dancing, 1994), notable for its uncharacteristically revealing conversation with Bausch on her creative process. In 2003, Choreographer and filmmaker Régis Obadia directed Dominique Mercy danse Pina (Dominique Mercy Dances Pina) for ARTE, an insightful focus on the first generation of Wuppertal dancers and Mercy’s long-standing friendship with Bausch.

Following numerous shorts, such as Coffee with Pina (Lee Yanor, 2006), the 2010s established an era of increasingly high-profile feature-length documentaries about the company that received wider distribution in cinemas. Rainer Hoffmann and Anne Linsel’s Tanzträume (Dancing Dreams, 2010) follows a collaboration with high school students from Wuppertal as they prepare to perform Bausch’s Kontakthof. The choreographer’s fondness for the young amateurs is apparent on camera in some of the last images of Bausch at work.

The choreographer’s sudden death in 2009 marked a turning point in the company that shifted the way that films would depict Tanztheater Wuppertal going forward. At the time, Wim Wenders, of “New German Cinema” fame, was in pre-production for a 3D film featuring Bausch’s dancers. That project became Pina (2011), capturing a singular transition at Tanztheater Wuppertal with grieving dancers speaking and moving in tribute to Bausch.

© «Les rêves dansants », Anne Linsel et Rainer Hoffman © Jour2fête distribution

© «Les rêves dansants », Anne Linsel et Rainer Hoffman © Jour2fête distribution

Questions related to the choreographer’s legacy that emerged in Pina find answers in the recent Dancing at Dusk: A Moment with Pina Bausch’s Rite of Spring (2020), a joint performance project of the Pina Bausch Foundation, École des Sables and Sadler’s Wells captured on film during the Coronavirus outbreak; and Florian Heinzen-Ziob’s Dancing Pina (2022). Both films demonstrate how Bausch’s work is being staged today on dancers outside Tanztheater Wuppertal. In the latter title, original cast members can be observed transmitting choreography with a respectful rigor while simultaneously allowing enough freedom for new performers to make the roles their own.

Celebrated auteurs and anonymous technicians alike have created this unintentional archive, providing humanist insights into the company and its founder as they transition through diverse phases of development. It bears witnesses not only to a growing choreographic repertoire and legacy, but to the evolution of the dancers and their relationships. In Dancing Pina, Malou Airaudo recalls Bausch’s artistic ethos: “We’re looking for who we are as humans”, a quest that easily transcends any creative borders between stage and screen.

Marisa C. Hayes writes about dance for a variety of publications, including Dance International, Dance Magazine, and Alternatives Théâtrales. Currently editor of The International Journal of Screendance, her academic research is focused on the relationship between dance and cinema. Her book Ju-on, published by Liverpool University Press, explores the influence of butoh dance in Takashi Shimizu’s eponymous film. She is currently a research supervisor in the Masters of Screendance at The Place – London Contemporary Dance School and co-directs the International Video Dance Festival of Burgundy.

Main image : « Dancing Pina », Florian Heinzen-Ziob © Dulac Distribution

One Day Pina Asked

Directed by Chantal Akerman

Available on VOD

https://www.centredufilmsurlart.com/films/un-jour-pina-a-demande/

Talk to Her

Directed by Pedro Almodovar

Available on DVD and VOD

https://www.lacinetek.com/fr/film/parle-avec-elle-pedro-almodovar-vod

Dominique Mercy Dances Pina

Directed by Régis Obadia

Available online

https://www.numeridanse.tv/videotheque-danse/dominique-mercy-danse-pina-bausch?s

It Did Not Stop, My Dancing

Directed by Eva-Elisabeth Fischer and Frieder Käsmann

Available online

https://www.pinabausch.org/post/it-did-not-stop-my-dancing

Dancing Dreams

Directed by Rainer Hoffmann and Anne Linsel

Available on DVD and VOD

https://boutique.arte.tv/detail/reves-dansants-sur-les-pas-de-pina-bausch

Pina

Directed by Wim Wenders

Available on DVD and VOD

https://vod.canalplus.com/cinema/pina/h/104090_40099

Dancing at Dusk: A Moment with Pina Bausch’s Rite of Spring

Available online

https://www.pinabausch.org/post/dancing-at-dusk

Dancing Pina

Directed by Florian Heinzen-Ziob

Available on VOD

https://boutique.arte.tv/detail/dancing-pina